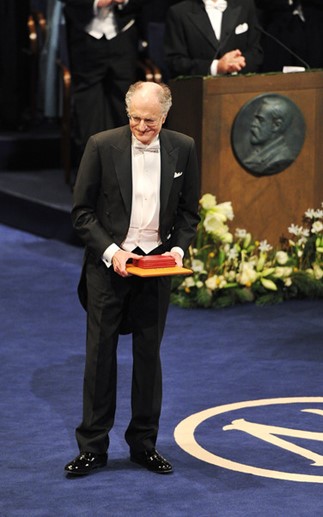

Many of the key issues about what modern macroeconomics has to say on global financial crises and deposit insurance are discussed in a 2010 interview with Thomas Sargent

Sargent said that two polar models of bank crises and what government lender-of-last-resort and deposit insurance do to arrest or promote them were used to understand the GFC. They are polar models because:

- in the Diamond-Dybvig and Bryant model of banking runs, deposit insurance and other bailouts are purely a good thing stopping panic-induced bank runs from ever starting; and

- in the Kareken and Wallace model, deposit insurance by governments and the lender-of-last-resort function of a central bank are purely a bad thing because moral hazard encourages risk taking unless there is regulation or there is proper surveillance and accurate risk-based pricing of the deposit insurance.

In the Diamond-Dybvig and Bryant model, if there is government-supplied deposit insurance, people do not initiate bank runs because they trust their deposits to be safe. There is no cost to the government for offering the deposit insurance because there are no bank runs! A major free lunch.

Tom Sargent considers that the Bryant-Diamond-Dybvig model has been very influential, in general, and among policy makers in 2008, in particular.

Governments saw Bryant-Diamond-Dybvig bank runs everywhere. The logic of this model persuaded many governments that if they could arrest the actual or potential runs by convincing creditors that their loans were insured, that could be done at little or no eventual cost to taxpayers.

In 2008, the Australian and New Zealand governments announced emergency bank deposit insurance guarantees. In Bryant-Diamond-Dybvig style bank panics, these guarantees ward off the bank run and thus should cost nothing fiscally because the deposit insurance is not called upon. These guarantees and lender of last resort function were seen as key stabilising measures. These guarantees were called upon in NZ to the tune of $2 billion.

- 1. The Diamond-Dybvig and Bryant model makes you sensitive to runs and optimistic about the ability of deposit insurance to cure them.

- The Kareken and Wallace model’s prediction is that if a government sets up deposit insurance and doesn’t regulate bank portfolios to prevent them from taking too much risk, the government is setting the stage for a financial crisis.

- The Kareken-Wallace model makes you very cautious about lender-of-last-resort facilities and very sensitive to the risk-taking activities of banks.

Kareken and Wallace called for much higher capital reserves for banks and more regulation to avoid future crises. This is not a new idea.

Sam Peltzman in the mid-1960s found that U.S. banks in the 1930s halved their capital ratios after the introduction of federal deposit insurance. FDR was initially opposed to deposit insurance because it would encourage greater risk taking by banks.

Late on Friday afternoon, Stuff posted an op-ed piece calling for the introduction of a (funded) deposit insurance scheme in New Zealand. It was written by Geof Mortlock, a former colleague of mine at the Reserve Bank, who has spent most of his career on banking risk issues, including having been heavily involved in the handling of the failure, and resulting statutory management, of DFC.

As the IMF recently reported, all European countries (advanced or emerging) and all advanced economies have deposit insurance, with the exception of San Marino, Israel and New Zealand. An increasing number of people have been calling for our politicians to rethink New Zealand’s stance in opposition to deposit insurance. I wrote about the issue myself just a couple of months ago, in response to some new material from the Reserve Bank which continues to oppose deposit insurance.

Different people emphasise different arguments in making the case for New Zealand to…

View original post 1,963 more words

Recent Comments