What is claimed to have gone wrong by the op-ed in The Guardian overnight?

A stark rich-poor divide, the OECD argued, had taken over a third off the country’s economic growth rate in the last 20 years. But how could this be?

The simple answer is that in the two decades from 1985 onwards, New Zealand had the biggest increase in income gaps of any developed country.

Incomes for the richest Kiwis doubled, while those of the poorest stagnated. Middle income earners didn’t do too well, either.

Are these claims true? That is, in the two decades from 1985 onwards, have the incomes of the richest Kiwis doubled, while those of the poorest stagnated and have a middle income earners not done too well either?

Figure 1 shows that prior to the recent recession starting in 2009, there were 15 years of steady growth in median household incomes. As will be shown, most of the period covered both by the op-ed in the Guardian, and by the OECD paper was an economic boom.

Figure 1: Real household income trends before housing costs (BHC) and after housing costs (AHC), 1982 to 2013 ($2013)

Source: Bryan Perry, Household incomes in New Zealand: Trends in indicators of inequality and hardship 1982 to 2013. Ministry of Social Development (July 2014).

Perry (2104) found that net income gains from the mid-1990s to 2013 were similar for all income groups, so income inequality in 2013 was also similar to the mid-1990s – see Figure 2.

Figure 2: Real household incomes (BHC), changes for top of income deciles, 1994 to 2013

![clip_image002[7] clip_image002[7]](https://utopiayouarestandinginit.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/clip_image0027_thumb.png?w=464&h=295)

Source: (Perry 2014).

Importantly, in the OECD analysis, much was made of what was happening to the 40% income decile. As can be seen from figure 2, this decile gained as much as any other group in New Zealand from the income growth between 1994 and 2013.

The Gini coefficient in figure 3 , which years the most common measure of inequality, shows no evidence of a rise in income inequality since the mid-1990s. The trend-line of the genie coefficient in figure 3 is almost flat since the early 1990s .

Figure 3: Gini coefficient New Zealand 1980-2015

Source: (Perry 2014).

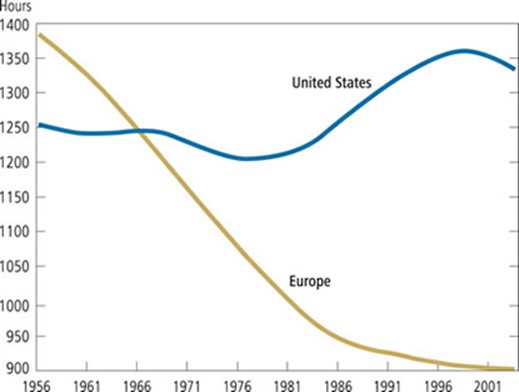

To make things more awkward, the large increase in income inequality in New Zealand in the late 1980s and early 1990s shown in figure 3 was followed by a 15 year economic boom after 20 years of economic stagnation – next to no income growth – as is shown in figure 4.

Figure 4: Real GDP per New Zealander and Australian aged 15-64, converted to 2013 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, 1956-2013

Source: Computed from OECD Stat Extract and The Conference Board, Total Database, January 2014, http://www.conference-board.org/economics

The lost decades of the growth in the 1970s and 1980s were replaced with a long boom. Trend growth of 2% per year returned after this increase in inequality – see figure 4.

The gains since the economic boom since the early 1990s has been broadly based both up and down the income distribution and by ethnicity. As shown in figure 5, between 1994 and 2010, real equivalised median household income rose 47% from 1994 to 2010; for Māori, this rise was 68%; for Pasifika, the rise was 77%.

Figure 5: Real equivalised median household income (before housing costs) by ethnicity, 1988 to 2013 ($2013).

![clip_image002[9] clip_image002[9]](https://utopiayouarestandinginit.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/clip_image0029_thumb2.png?w=457&h=301)

Source: (Perry 2014).

These improvements in Māori incomes since 1992 were based on rising Māori employment rates, fewer Māori on benefits, more Māori moving into higher paying jobs, and greater Māori educational attainment should be celebrated and consolidated. Māori unemployment reached a 20-year low of 8 per cent from 2005 to 2008.

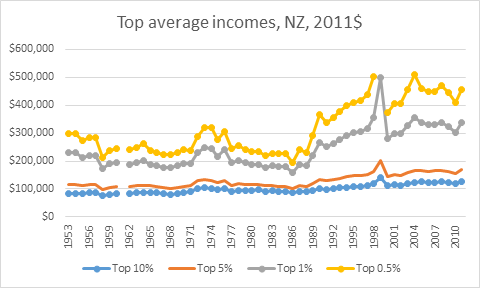

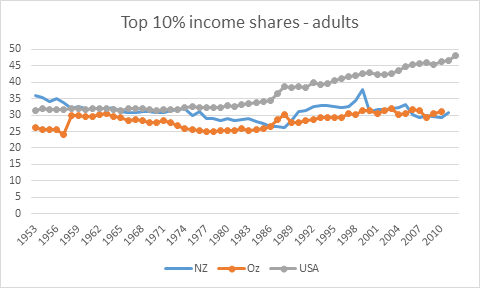

As for the top 1%, as shown by Figure 6, their income share has been steady at 8-9% since the mid-1990s. It was only in the USA the top 1% share continued to rise strongly, from 13% to 19%.

Figure 6: income shares of the top 1% of earners, New Zealand, Australia and USA

source: Top incomes database

Over the last more than two decades in New Zealand, there has been sustained income growth spread across all of society. Perry (2014) concluded that:

Overall, there is no evidence of any sustained rise or fall in inequality in the last two decades.

The level of household disposable income inequality in New Zealand is a little above the OECD median.

The share of total income received by the top 1% of individuals is at the low end of the OECD rankings.

What is claimed as the causes of this growing rich-poor divide that is also slowing growth by a third?

Tracing the causes of a growing income gap is like trying to map earthquake fault lines – never a precise science – but it is hard to ignore the correlation between the timing of the increase and the country’s post-1984 political revolution.

Embracing reforms known elsewhere as Thatchernomics and Reaganomics with unprecedented enthusiasm, New Zealand halved its top tax rate, cut benefits by up to a quarter of their value, and dramatically reduced the bargaining power – and therefore the share of national income – of ordinary workers.

Thousands of people lost their jobs as manufacturing work went overseas, and there was no significant response with increased trade training or skills programmes, a policy failure that is on-going.

At the same time, New Zealand stopped building affordable houses in any serious quantity, forcing poorer households to spend ever-increasing amounts on rent and mortgages.

As will be recalled from Figure 4, the economic reforms in New Zealand were followed by a long economic boom starting in 1992 that only came to an end with the onset of the global financial crisis.

Figure 7 shows that from 1994, the proportion of the lowest income households spending more than 30% of their income on housing fell steadily, reaching 34% by 204.

Figure 7: Proportion of households spending more than 30% of their income on housing costs by income quintile, New Zealand 1988–2013 HES years

Source: Perry (2014)

Housing affordability was improving for much of the period in which the op-ed in the Guardian was claiming it was getting worse. The increase in housing unaffordability in the late 1980s and early 1990s coincided with a deep recession and a cut in welfare benefits.

Housing affordability has become an issue in New Zealand because of rising prices. Supply is not keeping up with demand.

There were considerable increases in prices throughout the house price distribution between 2004 and 2008. Median house price increasing by over 50% between 2004 and 2008; the price rises were largest among the lower price houses.

It was not a case of a decline in demand under the hypothesis that is put forward in the op-ed in the Guardian. For that hypothesis to hold, housing prices would somehow have to fall in the price range of ordinary workers. That is not the case.

Furthermore, the large increase in housing prices and decline in housing affordability occurred a decade and more after the increase in inequality in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The timing is out.

Another inconvenience for the rich poor divide hypothesis is during the housing price boom after 2004 rent to disposable income for all income quintiles remained relatively constant. Rents were stable.

Poorer households are more likely to rent, and therefore much less likely to be affected by the housing affordability crisis in New Zealand as that was mostly about home ownership.

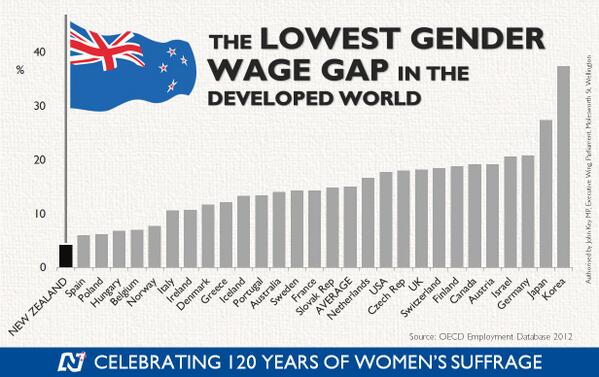

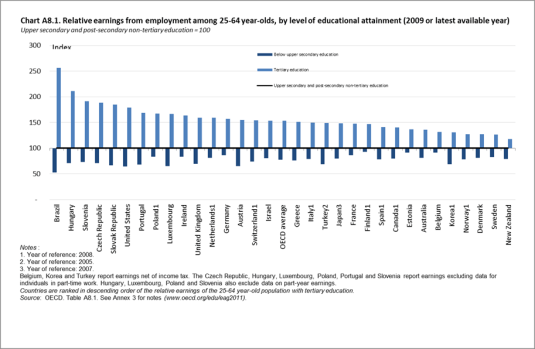

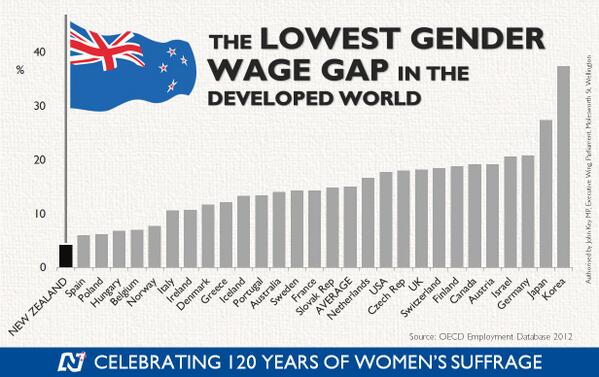

Gender analysis! Gender analysis? Where is the gender analysis? Over the last 20 to 30 years, the gender gap has closed substantially in terms of wages and employment. Young women now outnumber young men two to one at university.

New Zealand has the smallest gender wage gap in the Western world. That is inconsistent with the notion in New Zealand has a rich poor divide. Instead New Zealand appears to be an egalitarian paradise as long as you are not a boy!

The major driver of inequality in New Zealand and overseas is the rising number of two-income households made up of two well-educated parents and one or two children and many more single parent households on low pay or no one in paid employment in the house. Well-educated couples form into high income households; fewer of the less educated marry and too many end up a single mothers.

Source: closertogether.org.nz

The main cause of poverty in New Zealand is dependency on welfare benefits and in particular the number of single parents. Child poverty in beneficiary families is 75% to 80%, much higher than in families with at least one adult in full-time employment (11% in 2012 and 2013). The payment of welfare benefits to families who do not work guarantees an income to people not in a job, but it creates incentives not to work.

The economic and sociological literatures overseas increasingly suggesting that skill disparities resulting from a lower quality education and less access to good parenting, peer and neighbourhood environments produce most of the income gaps of racial and ethnic minorities rather than factors such as labour market discrimination.

via How New Zealand’s rich-poor divide killed its egalitarian paradise | Max Rashbrooke | Comment is free | The Guardian.

![clip_image002[7] clip_image002[7]](https://utopiayouarestandinginit.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/clip_image0027_thumb.png?w=464&h=295)

![clip_image002[9] clip_image002[9]](https://utopiayouarestandinginit.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/clip_image0029_thumb2.png?w=457&h=301)

![clip_image002[7] clip_image002[7]](https://utopiayouarestandinginit.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/clip_image0027_thumb1.png?w=412&h=264)

Recent Comments