The dangerous left-wing bias of economists strikes again

21 Sep 2015 2 Comments

in applied price theory, budget deficits, business cycles, economics of regulation, history of economic thought, occupational choice, politics - USA

The left-wing bias of economists must be taken into account in public policy-making. Any suggestions to regulate the economy, spend our way out of a recession, increase the top tax rate and so on must be discounted for that well-known but little publicised political bias.

Source: Economists Aren’t As Nonpartisan As We Think | FiveThirtyEight

As is not well-known enough, Cardiff and Klein (2005) used voter registration data to rank disciplines at Californian Ivy League universities by Democrat to Republican ratios. Economics is the most conservative social science, with a Democrat to Republican ratio of a mere 2.8 to 1. This can be contrasted with sociology (44 to 1), political science (6.5 to 1) and anthropology (10.5 to 1). 40% of Americans are Democrats, 32% are independents with the balance Republicans.

Zubin Jelveh, Bruce Kogut, and Suresh Naidu confirmed that bias: that the typical economist is a moderate Democrat. They found a 60–40 liberal conservative bias

Jelveh, Kogut, and Naidu also reminded, as many have before them that economics is the most politically diverse of academic professions. Sociology is a notorious left-wing echo chamber as an example. Their most likely view of Jeremy Corbyn is he is a bit of a Tory. Oddly enough, sociologists are the first to point the finger at economists for political bias.

Jelveh, Kogut, and Naidu correlated political donations of more than $200 in the Federal Elections Commission database with the language used in 18,000 journal articles back to the 1970s.

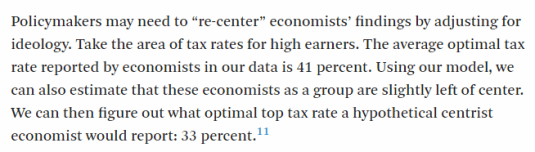

More interestingly, they correlated political bias with the estimates of quantitative effects such as the top tax rate and its impact on labour supply and investment:

We found a (significant) correlation when we compared the ideologies of authors with the numerical results in their papers. That means that a left-leaning economist is more likely to report numerical results aligned with liberal ideology (and the same is true for right-leaning economists and conservative ideology)… liberals think the fiscal multiplier is high, meaning the government can improve economic growth by increasing spending, while conservatives believe the multiplier is close to zero or negative.

They are not suggesting a rigging of the results. Economists tend to sort into the fields that suit their ideologies:

It’s more likely that these correlations are driven by research areas and the methodologies employed by economists of differing political stripe. Economics involves both methodological and normative judgments, and it is difficult to imagine that any social science could completely erase correlations between these two… macroeconomists and financial economists are more right-leaning on average while labour economists tend to be left-leaning. Economists at business schools, no matter their specialty, lean conservative. Apparently, there is “political sorting” in the academic labour market.

Before you start writing out the indictment that economic policy and the global financial crisis is the product of a vast left-wing conspiracy within the economics profession you should remember the wise words of George Stigler.

Stigler argued that ideas about economic reform needed to wait for a market. He contended that economists exert a minor and scarcely detectable independent influence on the societies in which they live. As is well known, Stigler in the 1970s toasted Milton Friedman at a dinner in his honour by saying:

Milton, if you hadn’t been born, it wouldn’t have made any difference.

Stigler said that if Richard Cobden had spoken only Yiddish, and with a stammer, and Robert Peel had been a narrow, stupid man, England would have still have repealed the Corn Laws in the 1840s. England would still have moved towards free trade in grain as its agricultural classes declined and its manufacturing and commercial classes grew in the 1840s onwards because of the industrial revolution.

As Stigler noted, when their day comes, economists seem to be the leaders of public opinion. But when the views of economists are not so congenial to the current requirements of special interest groups, these economists are left to be the writers of letters to the editor in provincial newspapers. These days, they would run an angry blog.

Alan Blinder and Fed Speak

18 Sep 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, macroeconomics, monetary economics, organisational economics Tags: central banks, cheap talk, credible commitments, economics of central banking, Fed speak, inflation targeting, The Fed

When President Clinton appointed Alan Blinder to be deputy chair of the Fed, his big hope was to find out what Alan Greenspan really thought rather than the public facade of gobbledygook. The term Fedspeak (also known as Greenspeak) is what Alan Blinder called "a turgid dialect of English" used by Federal Reserve Board chairmen in making wordy, vague, and ambiguous statements. Greenspan described it this way:

To Blinder’s astonishment, Alan Greenspan spoke just the same as he did at monetary policy meetings of the Fed as he did in public! Blinder never disagreed fundamentally with Greenspan about monetary policy.

The Fed Rate since 1955

18 Sep 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, economic history, macroeconomics, monetary economics Tags: monetary policy, The Fed

Greg Mankiw on the zero influence of modern macroeconomics on monetary policy making

17 Sep 2015 1 Comment

in business cycles, history of economic thought, inflation targeting, macroeconomics, managerial economics, monetarism, monetary economics, organisational economics Tags: Alan Blinder, Alan Greenspan, credible commitments, Greg Mankiw, modern macroeconomics, monetary policy, neo-Keynesian macroeconomics, new classical macroeconomics, The Fed, timing inconsistency

Two of my brothers studied economics in the early 1970s and then went on to different paths in law and computing respectively. If Greg Mankiw is right, my two older brothers could happily conduct a conversation with a modern central banker. Their 1970s macroeconomics, albeit batting for memory, would be enough for them to hold their own.

Source: AEAweb: JEP (20,4) p. 29 – The Macroeconomist as Scientist and Engineer – Greg Mankiw (2006).

I would spend my time arguing with a central banker that Milton Friedman may be right and central banks should be replaced with a computer. The success of inflation targeting is forcing me to think more deeply about that position. In particular the rise of pension fund socialism means that most voters are very adverse to inflation because of their retirement savings and that is before you consider housing costs are much largest proportions of household budgets these days.

Much higher house prices and the political sustainability of a return of inflation

13 Sep 2015 1 Comment

in business cycles, economic history, global financial crisis (GFC), inflation targeting, macroeconomics, monetary economics, politics - New Zealand, urban economics Tags: expressive voting, housing affordability, inflation rates, median voter theorem, mortgage belt, mortgage rates, rational ignorance, rational rationality

Mortgage interest rates were last in the double digits in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Since then, housing prices have exploded in New Zealand and barely paused for the recession in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis.

Source: International House Price Database – Dallas Fed; Housing prices deflated by personal consumption expenditure deflator.

With house prices and mortgages several times what they used to be, the ability for any household income to absorb the sudden return of high mortgage interest rates because of a return of even moderate CPI inflation and double-digit mortgage rates is well-nigh impossible, politically.

Source: Reserve Bank of New Zealand Mortgage rates and Bryan Perry, Household Incomes in New Zealand: trends in indicators of inequality and hardship 1982 to 2014 – Ministry of Social Development, Wellington (August 2015) Table C.5.

The chart above shows that the number of 25 to 44-year-olds in New Zealand who have more than 30% of their income going to housing expenses has doubled since 1988 to nearly a third of all households. The number of 45 to 64-year-olds who pay more than 30% of their income in housing expenses has quadrupled to 20%. That is a lot of voters who would be offended by mismanagement of monetary policy.

None of these households would have much left over to absorb an increasing mortgage interest rates. That is very different political arithmetic too the last time both mortgage rates and CPI inflation were in double digits, which was more than 20 years ago. Not many New Zealanders under the age of 40 or 45 have an adult memory of high inflation and high mortgage rates.

A history of interest rates

07 Sep 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, economic history, financial economics, macroeconomics, monetary economics Tags: central banking

The mancession

06 Sep 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, economic history, global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, job search and matching, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, unemployment Tags: reversing gender gap

How frequent are simultaneous financial crises in one country?

04 Sep 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, currency unions, development economics, economic growth, economic history, Euro crisis, financial economics, global financial crisis (GFC), great depression, great recession, growth disasters, growth miracles, law and economics, macroeconomics, monetary economics, property rights Tags: bank runs, banking crises, banking panics, currency crises, current account crises, debt crises, pseudo financial crises, real financial crises, sovereign debt crises, sovereign default

Longest time without a recession

02 Sep 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, economic growth, economic history, fiscal policy, global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, macroeconomics, monetary economics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: Australia, recessions and recoveries

Did Obama’s fiscal stimulus work?

30 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in budget deficits, business cycles, fiscal policy, great recession, macroeconomics, politics - USA Tags: fiscal stimulus, obama

Forecasting is not getting any easier

28 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in business cycles, financial economics, macroeconomics, monetary economics Tags: forecasting errors, monetary policy, The fatal conceit, The pretence to knowledge

Economists: They refuse to accept low interest rates! http://t.co/WyTlm6L1KS—

Tim Fernholz (@TimFernholz) August 18, 2015

The ups and downs of the Greek economy

25 Aug 2015 1 Comment

in budget deficits, business cycles, currency unions, economic history, Euro crisis, fiscal policy, macroeconomics, Public Choice, rentseeking Tags: Eurosclerosis, Greece, sovereign debt crisis, sovereign defaults

@ObsoleteDogma @rodrikdani http://t.co/xKx43wjWHy—

David Andolfatto (@dandolfa) June 30, 2015

Marginal tax rate of average earners in USA, UK, Australia and New Zealand since 2000

21 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, business cycles, economic growth, economic history, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, public economics Tags: Australia, British economy, productivity shocks, real business cycles, taxation and labour supply

Interesting to notice that in New Zealand and the USA after these increases in marginal tax rates on single taxpayers, their economies slowed down. What appears to have happened is a number of people reached the next income tax marginal tax rate threshold.

Source: OECD StatExtract.

Recent Comments