Operations Research and The Revolution in Aggregate Economics – Edward Prescott 2012

18 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, business cycles, economic growth, fiscal policy, global financial crisis (GFC), great depression, great recession, macroeconomics Tags: Edward Prescott, real business cycle theory

The extension of recursive methods to dynamic equilibrium modelling spawned a revolution in aggregate economics.

This revolution has resulted in aggregate economics becoming, like physics, a hard science and not exercises in storytelling.

Operations research played a major role in the development of practical methods to model dynamic aggregate economic phenomena and to predict the consequences of policy regimes.

Subsequently recursive methods were used to develop a quantitative theory of aggregate fluctuations and other aggregate phenomena.

Real GDP per New Zealander and Australian aged 15-64, PPP, 1956-2013, $US

18 Nov 2014 1 Comment

in business cycles, economic growth, geography, global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, macroeconomics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand Tags: lost decades, prosperity and depression

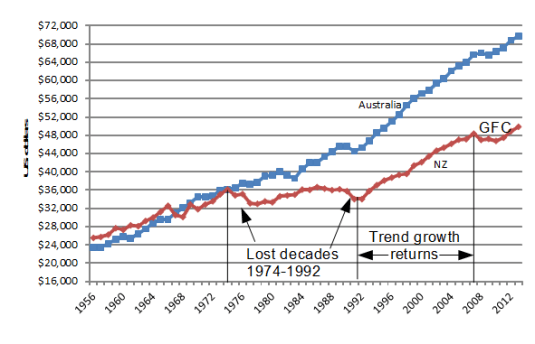

Figure 1: Real GDP per New Zealander and Australian aged 15-64, converted to 2013 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, 1956-2013, $US

Source: Computed from OECD Stat Extract and The Conference Board, Total Database, January 2014, http://www.conference-board.org/economics

Figure 1 shows that New Zealand lost two decades of growth between 1974 and 1992 after level pegging with Australia for the preceding two decades.

New Zealand returned to trend growth between 1992 and 2007. New Zealand did not make up the lost growth of the previous two decades to catch up to Australia.

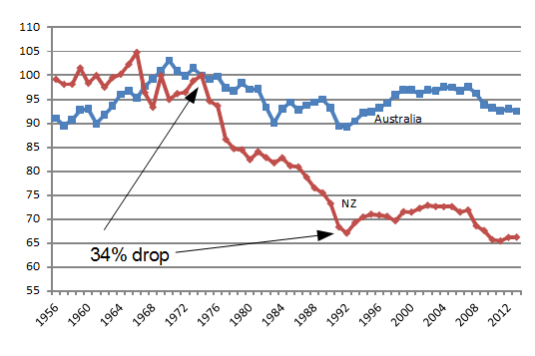

Figure 2: Real GDP per New Zealander and Australian aged 15-64, converted to 2013 price level with updated 2005 EKS purchasing power parities, 1.9 per cent detrended, base 100 = 1974, 1956-2013, $US

Source: Computed from OECD Stat Extract and The Conference Board, Total Database, January 2014, http://www.conference-board.org/economics

In Figure 2, a flat line equates to a 1.9% GDP annual growth rate; a falling line is a below trend growth rate; a rising line is an above 1.9% growth rate.

Figure 2 shows that there was a 34% drop against trend between 1974 and 1992; a return to trend growth and slightly better between 1992 and 2007; and then a recession to 2010.

Australia had its ups and downs since 1956 but essentially grew at the trend growth rate of 1.85% since 1970. The so-called resources boom in Australia does not show up in Figures 1 or 2.

There was no growth rebound in New Zealand to recover the lost ground, either in the lost decades between 1974 and 1992, or after the Global Financial Crisis. The strong GDP growth in Australia after that Keating recession in 1991 is an example of the country recovering lost ground after a recession – See Figure 2.

A trend growth rate of 1.9% is the 20th century trend growth rate that Edward Prescott currently estimates for the global industrial leader, which is the United States of America.

Sam Peltzman radio interview

17 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, business cycles, economics of regulation, history of economic thought, industrial organisation, law and economics, liberalism, macroeconomics, Sam Peltzman Tags: Sam Peltzman

Euroland and Japan compared since 2008

16 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

in budget deficits, business cycles, economic growth, global financial crisis (GFC), great recession Tags: Euroland, great recession, Japan, lost decades

Europe’s dismal economy

15 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, business cycles, Euro crisis, global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, macroeconomics Tags: Euroland, Euros crisis

Romer and Romer vs. Reinhart and Rogoff – MoneyBeat – WSJ

01 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

in business cycles, Euro crisis, global financial crisis (GFC), great depression, great recession, macroeconomics Tags: financial crises, GFC

Identifying financial crises after the fact is problematic: researchers will disagree on what their characteristics were, when they started and ended, and what actually counts as a crisis. This is particularly true of crises before World War II or involving developing economies, for which accurate data are harder to come by.

So the Romers created a measure of financial distress based on real-time accounts of developed-economy conditions prepared semiannually by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development between 1967 and 2007. And to check that the OECD wasn’t for some reason off-base on conditions, they crosschecked it with central bank annual reports and articles in The Wall Street Journal.

They then scored the severity of financial conditions from zero to 15, thus avoiding quibbles over what is and isn’t a crisis and allowing for more precise readings of economic effects.

Their finding: Declines in economic output, as measured by gross domestic product and industrial production, following crises were on average moderate and often short-lived. There was a lot of variation in outcomes, so there was nothing cut and dried about how economies respond to crises…

via Romer and Romer vs. Reinhart and Rogoff – MoneyBeat – WSJ.

Romers’ work suggests the poor performance of economies around the world in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis shouldn’t be cast as inevitable. In The Current Financial Crisis: What Should We Learn From the Great Depressions of the 20th Century? de Cordoba and Kehoe note that:

Kehoe and Prescott [2007] conclude that bad government policies are responsible for causing great depressions. In particular, they hypothesize that, while different sorts of shocks can lead to ordinary business cycle downturns, overreaction by the government can prolong and deepen the downturn, turning it into a depression.

An Open Letter to Paul Krugman | David K. Levine

31 Oct 2014 3 Comments

in budget deficits, business cycles, comparative institutional analysis, economics of religion, fiscal policy, global financial crisis (GFC), great recession, macroeconomics

A Perspective on Ireland’s Economy

19 Oct 2014 Leave a comment

in business cycles, fiscal policy, global financial crisis (GFC), macroeconomics, Public Choice Tags: GFC, Ireland

Dot point 4 is the key. The bank guarantee caused the depression.

Roger Kerr, New Zealand Business Roundtable Executive Director

Philip Lane is Professor of International Macroeconomics at Trinity College Dublin. He is also a managing editor of the journal Economic Policy, the founder of The Irish Economy blog, and a research fellow of the Centre for Economic Policy Research. His research interests include financial globalisation, the macroeconomics of exchange rates and capital flows, macroeconomic policy design, European Monetary Union, and the Irish economy.

Last week he visited New Zealand as a guest of the Treasury, the Reserve Bank, and Victoria University. During his visit he presented this guest lecture on the troubled Irish economy, drawing on his recent report to the Irish Parliament’s finance committee on ‘Macroeconomic Policy and Effective Fiscal and Economic Governance’.

Some highlights from his talk (also reported here by Brian Fallow in the New Zealand Herald) were:

- Ireland’s is a real depression: 15% fall in GDP 2007-2010

- The Celtic Tiger 1994-2001 was no…

View original post 216 more words

Earl A. Thompson on fiscal and monetary policy in the Great Recession

09 Oct 2014 Leave a comment

in budget deficits, business cycles, economic growth, fiscal policy, great recession, macroeconomics, monetary economics Tags: crowding out, Earl A. Thomson, fiscal policy, great depression, great recession, permanent income hypothesis, Ricardian equivalence

Recent Comments