Robert Lucas in a famous 1978 paper argued that all unemployment was voluntary because involuntary unemployment was a meaningless concept. He said as follows:

The worker who loses a good job in prosperous time does not volunteer to be in this situation: he has suffered a capital loss. Similarly, the firm which loses an experienced employee in depressed times suffers an undesirable capital loss.

Nevertheless the unemployed worker at any time can always find some job at once, and a firm can always fill a vacancy instantaneously. That neither typically does so by choice is not difficult to understand given the quality of the jobs and the employees which are easiest to find.

Thus there is an involuntary element in all unemployment, in the sense that no one chooses bad luck over good; there is also a voluntary element in all unemployment, in the sense that however miserable one’s current work options, one can always choose to accept them.

I agree that we all make choices subject to constraints. To say that a choice is involuntary because it is constrained by a scarcity of job-opportunities information is to say that choices are involuntary because there is scarcity.

Alchian said there are always plenty of jobs because to suppose the contrary suggests that scarcity has been abolished. Lucas elaborated further in 1987 in Models of Business Cycles:

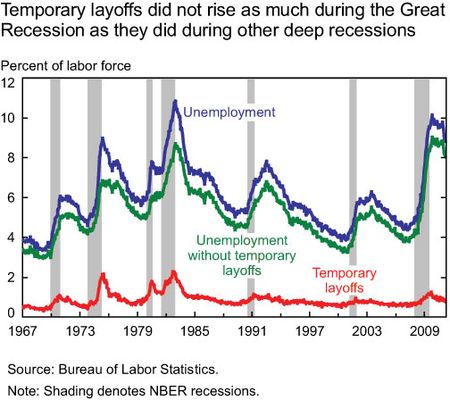

A theory that does deal successfully with unemployment needs to address two quite distinct problems.

One is the fact that job separations tend to take the form of unilateral decisions – a worker quits, or is laid off or fired – in which negotiations over wage rates play no explicit role.

The second is that workers who lose jobs, for whatever reason, typically pass through a period of unemployment instead of taking temporary work on the ‘spot’ labour market jobs that are readily available in any economy.

Of these, the second seems to me much the more important: it does not ‘explain’ why someone is unemployed to explain why he does not have a job with company X. After all, most employed people do not have jobs with company X either.

To explain why people allocate time to a particular activity – like unemployment – we need to know why they prefer it to all other available activities: to say that I am allergic to strawberries does not ‘explain’ why I drink coffee. Neither of these puzzles is easy to understand within a Walrasian framework, and it would be good to understand both of them better, but I suggest we begin by focusing on the second of the two.

Another way to understand unemployment is to use a device at the start of Alan Manning’s book on labour market monopsony:

What happens if an employer cuts the wage it pays its workers by one cent? Much of labour economics is built on the assumption that all existing workers immediately leave the firm as that is the implication of the assumption of perfect competition in the labour market.

In such a situation an employer faces a market wage for each type of labour determined by forces beyond its control at which any number of these workers can be hired but any attempt to pay a lower wage will result in the complete inability to hire any of them at all

Suppose workers offered to work for 1 cent. Would employers accept? Many do because they have intern and work experience programmes for students, but is this result of general application?

Understanding the reallocation of labour at the end of the recession requires careful attention to the 1980s writing of Alchian on the theory of the firm. Alchian and Woodward’s 1987 ‘Reflections on a theory of the firm’ says:

… the notion of a quickly equilibrating market price is baffling save in a very few markets. Imagine an employer and an employee. Will they renegotiate price every hour, or with every perceived change in circumstances?

If the employee is a waiter in a restaurant, would the waiter’s wage be renegotiated with every new customer? Would it be renegotiated to zero when no customers are present, and then back to a high level that would extract the entire customer value when a queue appears?

… But what is the right interval for renegotiation or change in price? The usual answer ‘as soon as demand or supply changes’ is uninformative.

Alchian and Woodward then go on to a long discussion of the role of protecting composite quasi-rents from dependent resources as the decider of the timing of wage and price revisions.

Alchian and Woodward explain unemployment as a side-effect of the purpose of wage and price rigidity, which is the prevention of hold-ups over dependent assets. They note that unemployment cannot be understood until an adequate theory of the firm explains the type of contracts the members of a firm make with one another.

My interpretation is the majority of employment relationships are capital intensive long-term contracts. Employers spend a lot of time searching and screening applicants to find those that will stay longer. In less skilled jobs, and in spot market jobs, employers will hire the best applicant quickly because job turnover costs are low. Back to Manning again:

That important frictions exist in the labour market seems undeniable: people go to the pub to celebrate when they get a job rather than greeting the news with the shrug of the shoulders that we might expect if labour markets were frictionless. And people go to the pub to drown their sorrows when they lose their job rather than picking up another one straight away. The importance of frictions has been recognized since at least the work of Stigler (1961, 1962).

Whatever may be among these frictions, wage rigidity is not one of them. Wages are flexible for job stayers and certainly new starters.

See What can wages and employment tell us about the UK’s productivity puzzle? by Richard Blundell, Claire Crawford and Wenchao Jin showing that in the recent UK recession 12% of employees in the same job as 12 months ago experienced wage freezes and 21% of workers in the same job as 12 months ago experienced wage cuts. Their data covered 80% of workers in the New Earnings Survey Panel Dataset.

Larger firms lay off workers; smaller firms tended to reduce wages. This British data showing widespread wage cuts dates back to the 1980s. Recent Irish data also shows extensive wage cuts among job stayers.

See too Chris Pissarides (2009), The Unemployment Volatility Puzzle: Is Wage Stickiness the Answer? arguing the wage stickiness is not the answer since wages in new job matches are highly flexible:

- wages of job changers are always substantially more procyclical than the wages of job stayers.

- the wages of job stayers, and even of those who remain in the same job with the same employer are still mildly procyclical.

- there is more procyclicality in the wages of stayers in Europe than in the United States.

- The procyclicality of job stayers’ wages is sometimes due to bonuses, and overtime pay but it still reflects a rise in the hourly cost of labour to the firm in cyclical peaks

How do existing firms who will not cut wages survive in competition with new firms who can start workers on lower wages? Industries with many short term jobs and seasonal jobs would suffer less from wage inflexibility.

Robert Barro (1977) pointed out that wage rigidity matters little because workers can, for example, agree in advance that they will work harder when there is more work to do—that is, when the demand for a firm’s product is high—and work less hard when there is little work. Stickiness of nominal wage rates does not necessarily cause errors in the determination of labour and production.

The ability to make long-term wage contracts and include clauses that guard against opportunistic wage cuts should make the parties better off. Workers will not sign these contracts if they are against their interests. Employers do not offer these contracts, and offer more flexible wage packages, will undercut employers who are more rigid. Furthermore many workers are on performance pay that link there must wages to the profitability of the company.

How can downward wage rigidity be a scientific hypothesis if extensive international evidence of widespread wage cuts since the 1980s and 30%+ of the workforce on performance bonuses is not enough to refute it?

Alchian and Kessel in “The Meaning and Validity of the Inflation-Induced Lag of Wages Behind Prices,” Amer. Econ. Rev. 50 [March 1960]:43-66) tested the hypothesis that workers suffered from money illusion by comparing the rates of return to firms in capital intensive industries with those of labour intensive industries. Labour intensive industries were not more profitable than capital intensive industries. Employers in labour intensive industries should profit from the misperceptions of workers about wages and future prices, but they did not. Alchian and Kessel found little evidence of a lag between wage and price changes.

In Canadian industries in the 1960s and 1970s, wage indexation ranged from zero to nearly 100%. Industries with little indexation should show substantial responses of real wage rates, employment and output to nominal shocks. Industries with lots of indexation would be affected little by nominal disturbances. Monetary shocks had positive effects but an industry’s response to these shocks bore no relation to the amount of indexation in the industry. Shaghil Ahmed (1987) found that those industries with lots of indexation were as likely as those with little indexation to respond to shocks.

If the signing of new wage contracts was important to wage rigidity, there should be unusual behaviour of employment and real wage rates just after these signings, but the results are mixed. Olivei and Tenreyro (2010) used the tendency of contracts to be signed at the start of years to show that monetary policy had significant effects in January but little effect in December because the effects were quickly undone.

Alchian (1969) lists three ways to adjust to unanticipated demand fluctuations:

• output adjustments;

• wage and price adjustments; and

• Inventories and queues (including reservations).

Alchian (1969) suggests that there is no reason for wage and price changes to be used regardless of the relative cost of these other options:

• The cost of output adjustment stems from the fact that marginal costs rise with output;

• The cost of price adjustment arises because uncertain prices and wages induce costly search by buyers and sellers seeking the best offer; and

• The third method of adjustment has holding and queuing costs.

There is a tendency for unpredicted price and wage changes to induce costly additional search. Long-term contracts including implicit contracts arise to share risks and curb opportunism over relationship-specific capital. These factors lead to queues, unemployment, spare capacity, layoffs, shortages, inventories and non-price rationing in conjunction with wage stability.

Recent Comments