HT: Antony Green.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

11 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in economic history, economics of media and culture, economics of regulation, public economics

HT: Antony Green.

10 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, Public Choice, public economics Tags: povertytraps, taxation and labour supply

09 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in Marxist economics, politics - USA, Public Choice, public economics

09 Feb 2016 1 Comment

in applied price theory, politics - USA, public economics

06 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in development economics, economics of regulation, entrepreneurship, fiscal policy, growth disasters, growth miracles, industrial organisation, labour economics, law and economics, macroeconomics, monetary economics, property rights, public economics Tags: capitalism and freedom, Chile, China, The Great Escape, Venezuela

06 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in economics of media and culture, fiscal policy, income redistribution, labour economics, labour supply, law and economics, poverty and inequality, property rights, public economics, rentseeking Tags: basic income, car racing, Finland, guaranteed minimum income, negative income tax

06 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in politics - USA, public economics Tags: 2016 presidential election, entrepreneurial alertness, growth of government, size of government, taxation and entrepreneurship, taxation and investment, taxation and labour supply

05 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in labour economics, labour supply, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, public economics Tags: 2016 presidential election, British election, Canada, Denmark, family tax credit, in work tax credit, taxation and labour supply

For some reason the Labour government in New Zealand in the mid-2000s could not bring itself to admit it was introducing a huge tax cut for families. To avoid admitting it ever gave a tax cut, that Labour government called the huge family tax credit introduced in 2004 and 2005 Working for Families.

Source: Taxing Wages 2015 – OECD 2015

The above data does not include the effects of GST and VAT.

05 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in economic history, labour economics, labour supply, politics - New Zealand, public economics

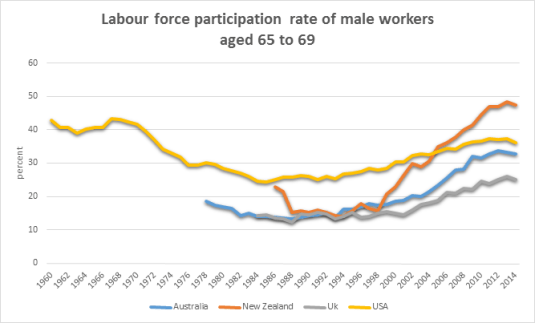

Up until the early 1990s, New Zealand had a universal old age pension that was paid from the age of 60. There was no means test or assets test. The eligibility age for this old age pension was increased to age 65 over the course of the 1990s and early 2000s. It obviously showed up in the labour supply of workers aged 66 and over in New Zealand after the change in the eligibility age.

Data extracted on 05 Feb 2016 04:49 UTC (GMT) from OECD.Stat.

05 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, economic history, labour economics, labour supply, politics - New Zealand, public economics

Up until the early 1990s, New Zealand had a universal old age pension that was paid from the age of 60. There was no means test or assets test. The eligibility age for this old age pension was increased to age 65 over the course of the 1990s and early 2000s. It obviously showed up in the labour supply of workers aged 60 to 64 in New Zealand both before and after the change in the eligibility age.

Data extracted on 05 Feb 2016 04:49 UTC (GMT) from OECD.Stat.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Scholarly commentary on law, economics, and more

Beatrice Cherrier's blog

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Why Evolution is True is a blog written by Jerry Coyne, centered on evolution and biology but also dealing with diverse topics like politics, culture, and cats.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

A rural perspective with a blue tint by Ele Ludemann

DPF's Kiwiblog - Fomenting Happy Mischief since 2003

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

The world's most viewed site on global warming and climate change

Tim Harding's writings on rationality, informal logic and skepticism

A window into Doc Freiberger's library

Let's examine hard decisions!

Commentary on monetary policy in the spirit of R. G. Hawtrey

Thoughts on public policy and the media

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Politics and the economy

A blog (primarily) on Canadian and Commonwealth political history and institutions

Reading between the lines, and underneath the hype.

Economics, and such stuff as dreams are made on

"The British constitution has always been puzzling, and always will be." --Queen Elizabeth II

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

WORLD WAR II, MUSIC, HISTORY, HOLOCAUST

Undisciplined scholar, recovering academic

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Res ipsa loquitur - The thing itself speaks

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Researching the House of Commons, 1832-1868

Articles and research from the History of Parliament Trust

Reflections on books and art

Posts on the History of Law, Crime, and Justice

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Exploring the Monarchs of Europe

Cutting edge science you can dice with

Small Steps Toward A Much Better World

“We do not believe any group of men adequate enough or wise enough to operate without scrutiny or without criticism. We know that the only way to avoid error is to detect it, that the only way to detect it is to be free to inquire. We know that in secrecy error undetected will flourish and subvert”. - J Robert Oppenheimer.

The truth about the great wind power fraud - we're not here to debate the wind industry, we're here to destroy it.

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Economics, public policy, monetary policy, financial regulation, with a New Zealand perspective

Celebrating humanity's flourishing through the spread of capitalism and the rule of law

Restraining Government in America and Around the World

Recent Comments