Our Treasury is at it again. Telling Kiwis a bleak future awaits them, especially in retirement. Its latest report about how NZ Demographic Change will affect the Country’s Finances is enough make the PM’s eyes glaze over, Finance Minister Willis fall asleep, NZ First leader Peters to press Delete on his laptop & everyone else…

The NZ Treasury’s Lack of Imagination Threatens our Future. It has no faith in Economic Magic (Einstein did).

The NZ Treasury’s Lack of Imagination Threatens our Future. It has no faith in Economic Magic (Einstein did).

07 Oct 2024 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, health economics, labour economics, labour supply, poverty and inequality, public economics, welfare reform Tags: retirement savings

Australian taxes on income are not particularly high if you include social security

02 Apr 2016 Leave a comment

in politics - Australia, public economics Tags: Australia, old age pensions, retirement savings, taxation and labour supply

Should the New Zealand superannuation fund try to beat the market?

09 Jun 2015 Leave a comment

in entrepreneurship, financial economics, politics - New Zealand Tags: active investing, ageing society, demographic crisis, efficient markets hypothesis, entrepreneurial alertness, New Zealand superannuation fund, old age pensions, passive investing, retirement savings

Most mutual funds still can't beat their benchmark read.bi/1GkTig1 http://t.co/r7ezoDGJbV—

BI Chart of the Day (@chartoftheday) June 03, 2015

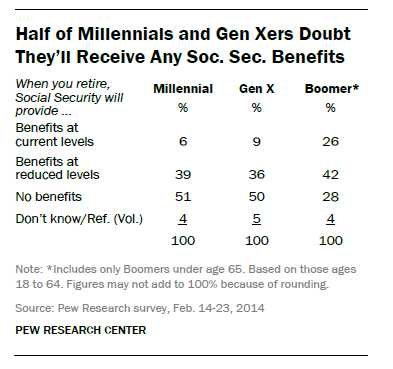

Ricardian equivalence alert: Millennials and the funding of their retirements

17 Feb 2015 5 Comments

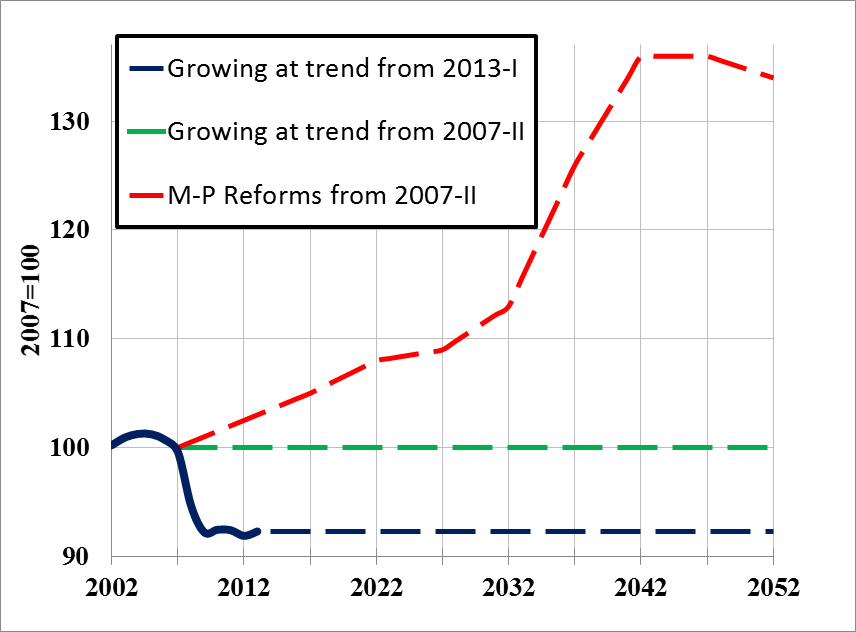

The path to higher U.S. prosperity

12 May 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, economic growth, Edward Prescott, great recession, labour economics, macroeconomics Tags: capital taxation, Edward Prescott, retirement savings, tax reform

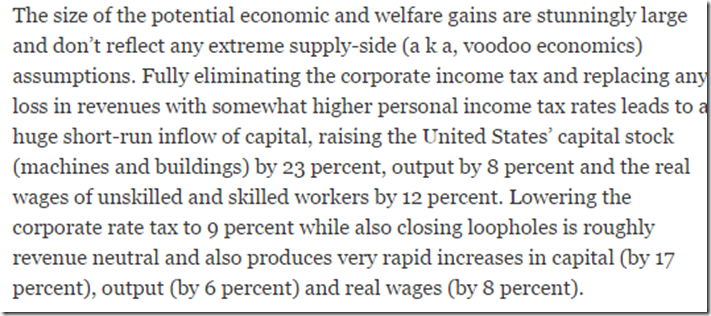

Suppose the USA:

- Had mandatory savings for retirement

- Eliminated capital income taxes

- Broadened tax base and lowered the marginal tax rate

- Phased in reforms so all birth-year cohorts are made better off

- Left welfare programs and local public good shares the same

- Savings not part of taxable income, saving withdrawals part of taxable income – with these changes U.S. income tax would be a consumption tax

US Detrended GDP per Capita

Source: Edward Prescott and Ellen McGrattan 2013.

Many people are far too smart to save for their retirements

01 May 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, macroeconomics Tags: Edward Prescott, fatal conceit, offsetting behavior, Other people are stupid fallacy, pretense to knowledge, retirement savings, time inconsistency

Which is better? Save for your retirement through the share market or save to own your own home and then present yourself at the local social security office to collect your taxpayer funded old-age pension?

Under this fine game of bluff, you bleed the taxpayer in your old age and pass on your debt-free home to your children.

This strategy is rational for the less well-paid. The family home is exempt from Income and asset testing for social security. If you lose you bet, sell your house and live off the capital.

For ordinary workers, this is a good bet. The middle class might prefer to live in a more luxurious retirement.

For ordinary workers, whose wages are not a lot more than their old age pension from the government, a government funded pension is a good political gamble. The old-age pension for a couple in New Zealand is set at no less that 60% of average earnings.

Compulsory savings for retirement requires the middle class to do what they can afford to do and would have done anyway.

Compulsory savings for retirement requires the working class to do what they can less afford to do.

Instead compulsory retirement savings deprives them of an old-age pension paid for by the taxes of the middle class.

In Australia, ordinary workers are required by law to save 9% of their wages for their retirements at 65 before they have had a chance to save for a car or a house or the rest of the condiments of life the middle class take for granted.

Edward Prescott argues for compulsory retirement savings account albeit with important twists because it is otherwise irrational for many to save for their retirement:

The reason we need to have mandatory retirement accounts is not because people are irrational, but precisely because they are perfectly rational — they know exactly what they are doing.

If, for example, somebody knows that they will be cared for in old age — even if they don’t save a nickel — then what is their incentive to save that nickel? Wouldn’t it be rational to spend that nickel instead?

…Without mandatory savings accounts we will not solve the time-inconsistency problem of people under-saving and becoming a welfare burden on their families and on the taxpayers. That’s exactly where we are now.

Prescott’s proposals are age specific. Those younger than 25 are not required to save anything because they are more pressing priorities such as buying cars and other consumer durables:

- Before age 25, workers would have no mandatory government retirement savings.

- Beginning at age 25, workers would contribute 3% vis-à-vis the current 10.6%.

- At age 30, that rate would increase to 5.3 percent.

- At 35, the rate would equal the full 10.6 percent.

- Upon retirement, there would be an annuity over the remaining lives of the individual and spouse

Most of all, the retirement savings must go into private savings accounts. These savings remain assets of the individual and therefore the compulsory savings requirements is not a tax and does not discourage labour supply, as Prescott explains:

Any system that taxes people when they are young and gives it back when they are old will have a negative impact on labour supply. People will simply work less.

Put another way: If people are in control of their own savings, and if their retirement is funded by savings rather than transfers, they will work more.

Prescott’s Nobel Prize jointly with Finn Kydland was for showing that policies are often plagued by problems of time inconsistency. They demonstrated that society could gain from prior commitment to economic policies.

Of course, as Tyler Cowen observed, forced savings schemes are easily offset by people rearranging their affairs, and they have their entire adult life to do so:

How much can our government force people to save in the first place?

You can make them lock up funds in an account, but they can respond by borrowing more on their credit cards, taking out a bigger mortgage, and in general investing less in their future.

People do not save for their retirements not because they are short-sighted, but because they are far-sighted. They know that governments will not carry out their threats and other big talk about not providing an adequate old-age pension.

The only way that governments can commit to not bailing people out who retire with no savings is to make them save for their own retirements over their working lives.

Some will be against this compulsion. Their opposition to compulsion cannot be based on opposition to the nanny state because that is faulty reasoning.

These opponents of compulsion and everyone else in the retirement income policy debate are playing in a far more complicated, decades long dynamic political game where ordinary people time and again out-smart conceited governments who pretend they know better:

The government has strategies.

The people have counter-strategies.

Ancient Chinese proverb

![image_thumb[3] image_thumb[3]](https://utopiayouarestandinginit.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/image_thumb3_thumb.png)

Recent Comments