#TPPANoWay @oxfamNZ @GreenpeaceUSA The Effects of Globalization

07 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, development economics, economic history, growth disasters, growth miracles, international economics, Marxist economics Tags: customs unions, expressive voting, free trade, Leftover Left, ODA, preferential trading agreements, rational ignorance, rational irrationality, The Great Escape, The Great Fact, TPA, TPPA, Twitter left, Tyler Cowen

Why Does 1% of History Have 99% of the Wealth? @Oxfam #TPPANoWay

06 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in development economics, economic history, growth disasters, growth miracles, history of economic thought, international economics Tags: capitalism and freedom, free trade, global poverty, globalisation, industrial revolution, international technology diffusion, technology diffusion, The Great Enrichment, The Great Fact, TPPA

Trading across the Mexican, Puerto Rican and US borders – World Bank Doing Business rankings, 2015

05 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in international economics, politics - USA

Tim Hazledine loses the plot when arguing for #TPPANoWay

03 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, economics of regulation, international economic law, international economics, politics - New Zealand

The op-ed by Tim Hazledine today made a poor case against the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement (TPPA). A much better case could be made but for his still fighting the 1990 election in New Zealand, which was about the future of economic reform.

He starts off strong by saying that the agreement is a mixed bag. I am of the same view. The TPPA is a so-so deal with small net gains.

Economic stuff the PM DIDNT mention #TPPANoWay @ItsOurFutureNZ @etangata @Mihi_Forbes @FoxMarama @grantrobertson1 https://t.co/L9rtd1dXvp—

Moana Maniapoto (@moanatribe) January 26, 2016

The TPPA and other trade agreements have dubious chapters such as the trade and environmental clauses, the intellectual property chapter and investor-state dispute settlement. Good arguments can be mounted against all of them, especially the inclusion of trade and environmental clauses into trade agreements.

Hazledine makes few of these points of mine, preferring instead to start with a rant against economic reform in New Zealand:

One of the more gormless of the 1980s “Rogernomics” economic policy experiments was to slash tariffs on imports without seeking equivalent concessions from our trading partners.

That didn’t do us much good then, but means now that matching reductions under the TPP is relatively painless for New Zealand, because our tariffs are already so low.

He wants to put tariffs back up again so that the poor pay well over the odds to import goods that are often not made in New Zealand and when they were they were very expensive.

Henry Simons argued that economics and in particular applied price theory is most useful both to the student and the political leader as a prophylactic against popular fallacies. Paul Krugman explained the twisted logic of trade negotiations well in this tradition when he said:

Anyone who has tried to make sense of international trade negotiations eventually realizes that they can only be understood by realizing that they are a game scored according to mercantilist rules, in which an increase in exports – no matter how expensive to produce in terms of other opportunities foregone – is a victory, and an increase in imports – no matter how many resources it releases for other uses – is a defeat.

The implicit mercantilist theory that underlies trade negotiations does not make sense on any level, indeed is inconsistent with simple adding-up constraints; but it nonetheless governs actual policy.

The economist who wants to influence that policy, as opposed to merely jeering at its foolishness, must not forget that the economic theory underlying trade negotiations is nonsense – but he must also be willing to think as the negotiators think, accepting for the sake of argument their view of the world.

The logic of trade negotiations is they are about cutting tariffs we should have cut long ago in return to others cutting their tariffs which they too should have cut long ago if they had any concern for the welfare of their own country rather than special interests.

Tim Hazledine swallows the logic of trade negotiations hook, line and sinker with all the enthusiasm of a non-economist but he is a professional economist. Professional economists laugh at the mercantilist logic of trade negotiations.

Paul Krugman summarised the TPPA well recently from a standpoint of a professional economist, which occasional he still is:

I’ve described myself as a lukewarm opponent of the Trans-Pacific Partnership; although I don’t share the intense dislike of many progressives, I’ve seen it as an agreement not really so much about trade as about strengthening intellectual property monopolies and corporate clout in dispute settlement — both arguably bad things, not good, even from an efficiency standpoint….

What I know so far: pharma is mad because the extension of property rights in biologics is much shorter than it wanted, tobacco is mad because it has been carved out of the dispute settlement deal, and Republicans in general are mad because the labour protection stuff is stronger than expected. All of these are good things from my point of view. I’ll need to do much more homework once the details are clearer.

Krugman then reminded that a trade agreement is most politically viable when it is most socially harmful. This is the point that the opponents of the TPPA miss. They will not want to discuss how some trade agreements are good deals but others are bad. That would admit that trade agreements can be welfare enhancing, and sometimes they are but sometimes not.

Hazledine’s op-ed improves noticeably when he talks about sovereignty but this will backfire on him as I will show shortly:

what perhaps most concerns TPP doubters is possible loss of sovereignty – control by legitimate New Zealand governments over New Zealand policies and institutions: Pharmac, mining, greenhouse gases, fracking, biomedical patents, the Treaty of Waitangi and others have been raised as being at risk. TPP supporters have attempted to soothe such concerns, but I’d say they should come clean. Of course the TPP will weaken New Zealand’s sovereignty. That is what these things are supposed to do!

The fundamental idea or ideology behind the TPP is that national governments cannot be trusted to act independently on many issues, because they will inevitably succumb to local vested interests. Only the cleansing discipline of untrammelled global free-market forces will deliver efficient outcomes.

I fully understand the economic logic of this position, and could easily myself compile a long list of harmful effects of local vested interests, at the top of which would actually be those Canadian etc dairy and other agricultural policies.

But the basic premise is flawed. Most of the sovereignty we are giving up is not ceded to the invisible hand of free, competitive markets. It is not even handed over to larger sovereign states, such as the United States. It is largely to be conceded in the cause of making the world a safer place for huge, stateless multinational corporations to roam. Are we sure this is what we want?

I agree that treaties reduce sovereignty. That is what they are about. I am particularly concerned about treaties that reduce New Zealand’s sovereignty over its greenhouse gas emissions. These sovereignty arguments against trade agreements apply equally to climate treaties.

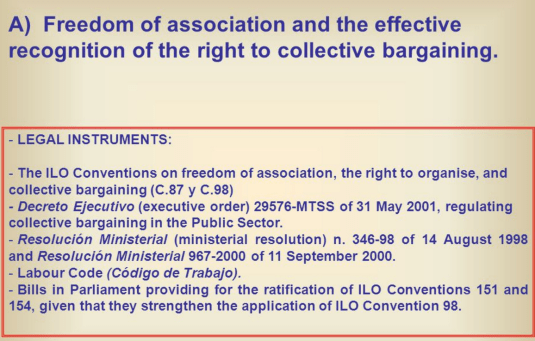

Likewise, trade agreements should not include trade and environmental standards as they limit the right of New Zealand to deregulate its labour market.

What's in the #TPP? Robust enforceable environmental protections. Get the facts ustr.gov/tpp #LeadOnTrade http://t.co/hzapJwGaCa—

USTR (@USTradeRep) October 05, 2015

What's in the #TPP? Protections for American workers. Get the facts: ustr.gov/tpp #MadeInAmerica http://t.co/VPeV70zaPT—

USTR (@USTradeRep) October 05, 2015

All too often unions point out that this or that International Labor Organisation convention signed decades ago conflicts with labour market deregulation. That undermines the sovereignty of New Zealand regarding the regulation of the economy just as much is the TPPA.

@GreenpeaceUSA I must photoshop this #TPPANoWay 4 climate treaties

02 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in environmental economics, global warming, international economic law, international economics, rentseeking

#TPPANoWay @janlogie @oxfamnz trade agreements and consolidating democracy

02 Feb 2016 Leave a comment

in constitutional political economy, development economics, economics of regulation, growth miracles, international economics, politics - New Zealand, Public Choice, rentseeking

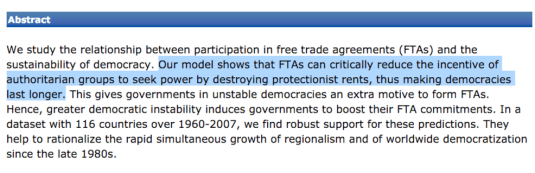

The key reason why China joined the World Trade Organisation and other trade agreements is to bring some semblance of law to an authoritarian country.

Source: AEAweb: AEJ: Macro (6,2) p. 29 – Free Trade Agreements and the Consolidation of Democracy via Max Roser.

Both the elites and ordinary people are prospering tremendously from the rise of capitalism in China, Vietnam and other places. A move away from this liberalisation to a more authoritarian setting would cost too many people too much money.

In the course of these economic liberalisations, China and Vietnam, for example, changed from totalitarian dictatorships to tin-pot dictatorships. As long as you keep out of politics in these countries, there is a fair degree of freedom and much more freedom compared to the days of communism.

Percentage employed in agriculture in the world's major economies over the last 50 years. https://t.co/UbaDnaE8Lr—

Robert Wilson (@CountCarbon) January 08, 2016

@TrevorMallard what next for #TPPANoWay? Repeal CER?

31 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in economic history, international economics, International law, law and economics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, Public Choice, television, TV shows Tags: CER, closer economic relations, Hollywood economics, ISDS, preferential trading agreements, rational irrationality, single market, TPPA, Twitter left

New Zealand filmmakers have used trade treaties to pry open access to foreign markets by challenging failures to honour promises of nondiscrimination in trade and investment in the Federal Court of Australia.

This should please the Twitter Left because they are also a film going left as are most members of the educated middle class as a point of identity and snobbery.

Back in the day, New Zealand television programming was sold cheaply into the Australian market. Many cultural and other products are exported into foreign markets and sold for whatever they can get above the price of shipping or digital transmission. What else explains all that rubbish on cable TV?

Under the Closer Economic Relations agreement that creates a single market between Australia and New Zealand, New Zealand made television programming content must be treated the same way as Australian content so it was included in their 50% local content rules for commercial television back from whenever I remember this story from.

There was a Federal Court of Australia case that ruled that New Zealand television programming was Australian content programming for the purposes of the relevant media regulations because of Closer Economic Relations.

From the late 1990s, with revival of the New Zealand film and television industry, New Zealand content was starting to flood the Australian market, especially in the off-season in the summer when stations were looking for cheap content to fill a low ratings period.

Naturally, this Kiwi invasion did not please the rent seeking Australian television programme production industry and many a mendicant actor, writer and producer

Where there is a will, where there is a way: minimum quality standards are introduced into the Australian content rules defined by price – a price that happen to be above what the television stations used to pay for New Zealand made programming in the off-season.

This court victory in favour of various New Zealand film industry in enforcing a trade and investment treaty puts the Twitter left in a bit of a conundrum. Which is more important? The New Zealand film industry or their hatred of globalisation and the rule of law.

The 1st @NYTimeskrugman on #TPPANoWay @Oxfamnz #JaneKelsey

30 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, development economics, economic history, growth disasters, growth miracles, international economics Tags: customs unions, free trade agreements, globalisation, Jane Kelsey, Leftover Left, Oxfam, Paul Krugman, preferential trading agreements, rational irrationality, TPP, Twitter left, Yes Minister

https://twitter.com/TPPMediaMarch/status/692055631579185152

If George Bush had not won the 2000 presidential election, Paul Krugman would have taken over as the best communicator of economics since Milton Friedman. Instead, he became patient number no.1 of George Bush derangement syndrome. Ann Coulter was patient no. 1 of Clintons derangement syndrome.

Source: Enemies of the WTO.

Development & Trade: Empirical Evidence @DavidShearerMP @oxfamnz @TPPANoWay

29 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, development economics, economic history, growth disasters, growth miracles, international economics, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: free trade, free trade agreements, preferential trading agreements, The Great Enrichment, The Great Fact, TPPA, WTO

@realdonaldtrump is wrong in tariffs

26 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economic history, international economics, politics - USA Tags: 2016 presidential election, China, tariffs, trade wars

Globalisation is Good – Johan Norberg on Globalisation

23 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, development economics, economic history, growth miracles, international economics, Marxist economics Tags: capitalism and freedom, extreme poverty, global poverty, globalisation, The Great Escape, The Great Fact

@greencatherine @cjsbishop Logic of #BDS refutes @TPPANoWay

23 Jan 2016 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, development economics, economic history, international economic law, international economics, politics - New Zealand, Public Choice

If our friends on the left are to be believed, trade liberalisation is bad unless it involves Cuba, Vietnam, Iraq and other heroes of the anti-west left. The anti-west left is different from the antifascist left and is sometimes known as the renegade left or regressive left.

Access to world markets, and the removal of trade sanctions and travel and investment restrictions are all to the benefit of the Vietnamese, Iraqi and Cuban people in the street and not just their elites in the eyes of the anti-west left. There you have: trade liberalisation is bad because reduced tariffs at home and abroad hurts ordinary people; trade sanctions are bad because they hurt ordinary people by denying them access to import from and exporting into world markets.

Trade sanctions against Iraq were to terrible for the Iraqi people. Removing those trade sanctions and similar sanctions on Cuba and Vietnam, which expanded their ability to export and import was essential to improving the welfare of Iraqis, Cubans and Vietnamese respectively. Two of these three countries are not a democracy with the guarantees elections have in ensuring broad-based benefits but nonetheless greater trade liberalisation was seen as to the advantage of the ordinary people of those dictatorships by the Left.

https://twitter.com/GazaReports/status/686399912485994496

Likewise boycotting, disinvesting and sanctions on Israel will change the Israeli policy because the Israeli people. The logic here is that trade and investment is wealth enhancing, so restricting trade punishes Israelis.

Source: Kennedy, New Zealand Greens: Tipping points – Israel, Palestine, and peace.

A comprehensive study by Kim Elliott, Jeffrey Schott, and Gary Hufbauer looked at whether sanction works. Do they accomplish the goals identified by U.S. policy-makers such as ending apartheid or undermining Libya’s support of terrorism? The study estimated they have succeeded 23 percent of the time. But of course as Kaempfer and Lowenberg say

Sanctions may be imposed not to bring about maximum economic damage to the target, but for expressive or demonstrative purposes. Moreover, the political effects of sanctions on the target nation are sometimes perverse, generating increased levels of political resistance to the sanctioners’ demands.

It is also that case that Kaempfer, Lowenberg and Mertens (2001) found that sanctions generate rents that can be appropriated by a dictator and his cronies and supporters such as those who were close to Saddam. The losses from the sanctions were borne by those who are opposed to the regime. This weakens their capacity to oppose it, leading to the further entrenchment in power of the dictator and his supporters. As Wintrobe explains:

In the public choice approach, sanctions work through their impact on the relative power of interest groups in the target country. An important implication of this approach is that sanctions only work if there is a relatively well organized interest group whose political effectiveness can be enhanced as a consequence of the sanctions.

What is reasonably clear from the literature on the economics of trade sanctions is at ordinary people in both dictatorships and democracies suffer from trade sanctions the most. The political elite can shift the costs of the trade and investment sanctions onto the disenfranchised within their country. Those with political connections have a better chance of minimising the costs and profiting from any windfall rents:

as Galtung (1967) observes, sanctions can be counterproductive by giving rise to a new elite in the target nation that benefits from international isolation. For example, Selden (1999) notes that, in the long run, sanctions often foster the development of domestic industries in the target country, thus reducing the target’s dependence on the outside world and the ability of sanctioners to influence the target’s behaviour through economic coercion…

Damrosch (1993, p. 299) contends that sanctions will almost inevitably benefit an autocratic regime because the regime will always be in a better position than the civilian population to control external transactions and the internal economy. In Damrosch’s view, the creation and enrichment of a criminal class that profiteers from trading bootleg or scarce goods means that even the most skilfully targeted sanctions will serve only to entrench the power of the ruling elite

One of the hopefully unintended consequences of trade and investment sanctions is disinvestment entrenches the position of capitalists in the sanctioned country and raises the rate of return on the capital in the targeted country as Kaempfer and Lowenberg again found:

…disinvestment sanctions can have the perverse effect of enhancing the target country’s ability to pursue its objectionable behaviour. The existing foreign capital stock – the physical plant and capacity previously owned by foreigners – is purchased by domestic capital owners at reduced prices, causing yields to rise and prompting target-country residents to sell foreign assets and substitute into domestic assets with higher rates of return.

The increase in the rate of return due to the acquisition of productive assets at fire-sale prices translates into a windfall gain to domestic capital owners, which increases the tax base available to the government to finance its policies, including those that attracted the sanctions in the first place

So far so good in terms of international economics of the renegade left until we start considering their attitude to trade agreement such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership. The logic of BDS is swept aside as is the rationale for opposing trade sanctions against Iraq, Cuba and Vietnam. Now enhanced opportunities for trade and investment is not in the interests of ordinary people even if they are Vietnamese – the biggest winner from the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Now increased opportunities to export are a bad thing. Investor state dispute settlement procedures, which were initially proposed by the governments of poor countries such as in South America, which offer a relief to foreign investors against expropriation and discrimination become a bad thing. Safeguards against corrupt and venial developing country politicians, bureaucrats and courts expropriating foreign investors are a bad thing even if you are talking about Vietnam or Cuba.

The Greens are the first to call for trade sanctions as an alternative to military intervention. Trade sanctions on the grounds of human rights violations as far back apartheid in South Africa make no sense unless the reduced access to world markets imposes a cost on a country. In the case of a democracy like Israel, trade sanctions must hurt the man in the street otherwise the sanctions will not shift electoral fortunes.

The last line of defence of the trade sanctions work but trade liberalisation is bad line of thought is most of the profits and losses of both trade sanctions and trade liberalisations fall on the elite. It is a trickle up argument.

The first flow in that argument is the sanctions against apartheid in South Africa and Rhodesia. They were aimed at ordinary people such as those that play and watch cricket, rugby and other sports. The idea is to encourage people to change their political views and votes if they want access to global sport.

Both Rhodesia and South Africa were democracies for whites. White settler politics in Rhodesia was particularly colourful. It was a brave man to make any statement that put him at the risk of being overtaken on his right in white settler politics.

The bigger problem for the trade sanctions are good, trade liberalisation is bad argument comes from the interest group based explanations of industrialisation in Japan and the East Asian Tigers. Economic development often comes to developing countries through export based industrialisation.

The reason that export based industrialisation is a common path to economic development for poor countries is it does not threaten the existing configuration of special interests. It does not involve deregulating any domestic industry. The export industries do not threaten the business interests and profits of existing rent seekers and ruling elites.

Post-war trade liberalisation and tariff cuts gave Korean and the other East Asian Tigers much greater access to major export markets. This allowed export production to expand without limit. This expansion did not threaten local special interests because they kept their privileges and barriers to entry into the domestic markets.

Incumbent suppliers and workers are less likely to be hurt by the adoption of more efficient technologies because output expands greatly through exporting. If a market is small and limited to one country, and output cannot be increased without price cuts, greater production efficiency from a new technology can lead to less employment and business closures. Industry insiders may oppose this. Exporting reduce the incentives for insiders to block more efficient technologies (Parente and Prescott 2005; Holmes and Schmitz 1995; Olson 1982). Distributional coalitions slow down a society’s capacity to adopt new technologies and to reallocate resources in response to changing conditions and thereby reduce the rate of economic growth.

Many other under-developed nations did not grow because institutional sclerosis locked them into yesterday’s technologies and industries with low growth and major declines in relative incomes (Olson 1982, 1984; Heckelman 2007; Bischoff 2007). A growing accumulation of distributional coalitions – institutional sclerosis – slowed down the capacity of these under-developed countries to adopt new technologies and reallocate resources across firms and industries in response to changing conditions and new opportunities (Olson 1982, 1984; Acemoglu and Robinson 2005).

Mancur Olson argued that over time, stable societies accumulate “distributional coalitions,” narrow special-interest organizations that burden the economy with overregulation and opaque forms of wealth redistribution.

Latin America is a good example of stagnation after initial prosperity because of the accumulation of barriers to efficient production. Latin America has many more international and domestic barriers to competition than do Western and the successful East Asian countries (Cole et al. 2005).

Institutional reforms and imported new technologies increased employment and incomes through this explosion in exporting in Japan and the newly industrialised countries in East Asia. This allowed the losers from the economic changes to be compensated directly or with new opportunities in the export sectors (Parente and Prescott 1999, 2005; Olson 1982, 1984; Acemoglu and Robinson 2005).

The argument that trade sanctions are good while trade liberalisation is bad simply does not stand up against the economic history of trade sanctions, trade liberalisation and export-led industrialisation. If they did, the economic histories of Latin America and East Asia would swap. Latin America took the path of import substitution and crony capitalism while East Asia chose export led industrialisation, low taxes and the market economy.

Recent Comments