Robert Lucas on Depression era policies and current financial crisis

14 Dec 2014 Leave a comment

in global financial crisis (GFC), great depression, great recession, macroeconomics, Robert E. Lucas Tags: great depression, great recession, Robert Lucas

Involuntary unemployment and the great vacation theories of the great depression and Eurosclerosis – updated again

10 Dec 2014 1 Comment

in economic growth, Edward Prescott, Euro crisis, great depression, job search and matching, labour economics, macroeconomics, Robert E. Lucas, unemployment Tags: Eurosclerosis, great depression, voluntary unemployment

Most Keynesian economists are convinced that something exists called involuntary unemployment and people can be unemployed through no fault of their own. They will accept the going wage but no employer is willing to offer it to them.

Lucas and Rapping’s (1969) paper, “Real Wages, Employment, and Inflation” provides the micro-foundations for an analysis of the labour suppl. They felt the need to reconcile the existence of unemployment with market clearing and referred to recent work of Armen Alchian (1969) on search explanations of unemployment.

Lucas and Rapping viewed unemployment as voluntary, including the mass unemployment during the great depression (Lucas and Rapping 1969: 748).

Lucas and-Rapping viewed current labour demand as a negative function of the current real wage. Current labour supply was a positive function of the real wage and the expected real interest rate, but a negative function of the expected future wage.

Under their framework, if workers expect higher real wages in the future or a lower real interest rate, current labour supply would be depressed, employment would fall, unemployment rise, and real wages increase.

Lucas and Rapping depicted labour suppliers as rational optimisers who engaged in inter-temporal substitution: working more when current wages were high relative to expected wages. The prevailing Keynesian approach assumed labour supply was passive, and movements in the demand for labour determined changes in employment.

Lucas and Rapping offered an unemployment equation relating the unemployment rate to actual versus anticipated nominal wages, and actual versus anticipated price levels. Unemployment could be the product of expectational errors about wages.

Lucas and Rapping’s model was poor at explaining unemployment after 1933 in terms of job search and expectational errors.

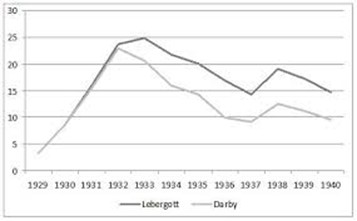

The graph below shows two different series for unemployment in the 1930s in the USA: the official BLS level by Lebergott; and a data series constructed famously by Darby. Darby includes workers in the emergency government labour force as employed – the most important being the Civil Works Administration (CWA) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

Once these workfare programs are accounted for, the level of U.S. unemployment fell from 22.9% in 1932 to 9.1% in 1937, a reduction of 13.8%. For 1934-1941, the corrected unemployment levels are reduced by two to three-and-a half million people and the unemployment rates by 4 to 7 percentage points after 1933.

Not surprisingly, Darby titled his 1976 Journal of Political Economy article Three-and-a-Half Million U.S. Employees Have Been Mislaid: Or, an Explanation of Unemployment, 1934-1941.

The corrected data by Darby shows stronger movement toward the natural unemployment rate after 1933. Darby concluded that his corrected date are suggests that the unemployment rate was well explained by a job search model such as that by Lucas and Rapping together with the wage fixing under the New Deal that kept real wages up and unemployment high.

Both the Keynesian approach to unemployment and the job search approach to unemployment view workers in emergency government work programs as employed and not as unemployed.

In the late 1970s, Modigliani dismissed the new classical explanation of the U.S. great depression in which the 1930s unemployment was mass voluntary unemployment as follows:

Sargent (1976) has attempted to remedy this fatal flaw by hypothesizing that the persistent and large fluctuations in unemployment reflect merely corresponding swings in the natural rate itself.

In other words, what happened to the U.S. in the 1930’s was a severe attack of contagious laziness!

I can only say that, despite Sargent’s ingenuity, neither I nor, I expect most others at least of the nonMonetarist persuasion,. are quite ready yet. to turn over the field of economic fluctuations to the social psychologist!

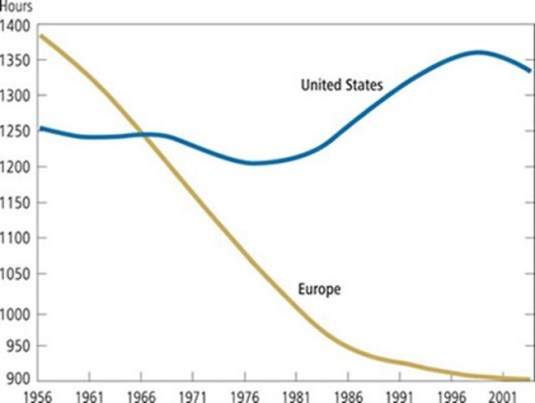

As Prescott has pointed out, the USA in the Great Depression and France since the 1970s both had 30% drops in hours worked per adult. That is why Prescott refers to France’s economy as depressed. The reason for the depressed state of the French (and German) economies is taxes, according to Prescott:

Virtually all of the large differences between U.S. labour supply and those of Germany and France are due to differences in tax systems.

Europeans face higher tax rates than Americans, and European tax rates have risen significantly over the past several decades.

In the 1960s, the number of hours worked was about the same. Since then, the number of hours has stayed level in the United States, while it has declined substantially in Europe. Countries with high tax rates devote less time to market work, but more time to home activities, such as cooking and cleaning. The European services sector is much smaller than in the USA.

Time use studies find that lower hours of market work in Europe is entirely offset by higher hours of home production, implying that Europeans do not enjoy more leisure than Americans despite the widespread impression that they do.

Richard Rogerson, 2007 in “Taxation and market work: is Scandinavia an outlier?” found that how the government spends tax revenues when assessing the effects of tax rates on aggregate hours of market work:

- Different forms of government spending imply different elasticities of hours of work with regard to tax rates;

- While tax rates are highest in Scandinavia, hours worked in Scandinavia are significantly higher than they are in Continental Europe with differences in the form of government spending can potentially account for this pattern; and

- There is a much higher rate of government employment and greater expenditures on child and elderly care in Scandinavia.

Examining how tax revenue is spent is central to understanding labour supply effects:

- If higher taxes fund disability payments which may only be received when not in work, the effect on hours worked is greater relative to a lump-sum transfer; and

- If higher taxes subsidise day care for individuals who work, then the effect on hours of work will be less than under the lump-sum transfer case.

Others such as Blanchard attribute the much lower labour force participation in the EU since the 1970s to their greater preference for leisure in Europe. An increased preference for leisure is another name for voluntary unemployment.

The lower labour force participation in higher unemployment in Europe is voluntary because of the higher demand for leisure among Europeans. According to Blanchard:

The main difference [between the continents] is that Europe has used some of the increase in productivity to increase leisure rather than income, while the U.S. has done the opposite.

An unusual left-right unity ticket emerged to explain the great depression in the 1930s and the depressed EU economies from the 1970s: the great vacation theory.

Operations Research and The Revolution in Aggregate Economics – Edward Prescott 2012

18 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

in applied welfare economics, business cycles, economic growth, fiscal policy, global financial crisis (GFC), great depression, great recession, macroeconomics Tags: Edward Prescott, real business cycle theory

The extension of recursive methods to dynamic equilibrium modelling spawned a revolution in aggregate economics.

This revolution has resulted in aggregate economics becoming, like physics, a hard science and not exercises in storytelling.

Operations research played a major role in the development of practical methods to model dynamic aggregate economic phenomena and to predict the consequences of policy regimes.

Subsequently recursive methods were used to develop a quantitative theory of aggregate fluctuations and other aggregate phenomena.

The Greek great depression

15 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

in Euro crisis, global financial crisis (GFC), great depression, great recession, macroeconomics, politics Tags: euro crisis, Euroland, Greece

Romer and Romer vs. Reinhart and Rogoff – MoneyBeat – WSJ

01 Nov 2014 Leave a comment

in business cycles, Euro crisis, global financial crisis (GFC), great depression, great recession, macroeconomics Tags: financial crises, GFC

Identifying financial crises after the fact is problematic: researchers will disagree on what their characteristics were, when they started and ended, and what actually counts as a crisis. This is particularly true of crises before World War II or involving developing economies, for which accurate data are harder to come by.

So the Romers created a measure of financial distress based on real-time accounts of developed-economy conditions prepared semiannually by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development between 1967 and 2007. And to check that the OECD wasn’t for some reason off-base on conditions, they crosschecked it with central bank annual reports and articles in The Wall Street Journal.

They then scored the severity of financial conditions from zero to 15, thus avoiding quibbles over what is and isn’t a crisis and allowing for more precise readings of economic effects.

Their finding: Declines in economic output, as measured by gross domestic product and industrial production, following crises were on average moderate and often short-lived. There was a lot of variation in outcomes, so there was nothing cut and dried about how economies respond to crises…

via Romer and Romer vs. Reinhart and Rogoff – MoneyBeat – WSJ.

Romers’ work suggests the poor performance of economies around the world in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis shouldn’t be cast as inevitable. In The Current Financial Crisis: What Should We Learn From the Great Depressions of the 20th Century? de Cordoba and Kehoe note that:

Kehoe and Prescott [2007] conclude that bad government policies are responsible for causing great depressions. In particular, they hypothesize that, while different sorts of shocks can lead to ordinary business cycle downturns, overreaction by the government can prolong and deepen the downturn, turning it into a depression.

Some graphs on the great deviation on both sides of the Atlantic

31 Oct 2014 Leave a comment

in economic growth, Euro crisis, fiscal policy, global financial crisis (GFC), great depression, macroeconomics Tags: Eurosclerosis, GFC, Great Geviation, great recession

Figure 1: Actual and potential GDP in the US

Sources: Congressional Budget Office, Bureau of Economic Analysis

Figure 2: Actual and potential GDP in the Eurozone

Sources: IMF World Economic Outlook Databases, Bloomberg

HT: Larry Summers

Hayek Explains Why He Did Not Challenge Keynes’ General Theory

03 Sep 2014 Leave a comment

in Austrian economics, business cycles, F.A. Hayek, fiscal policy, great depression, macroeconomics Tags: FA Hayek, General Theory, Keynes

Eugene Fama and the simulative effects of fiscal policy

31 Jul 2014 6 Comments

in budget deficits, fiscal policy, great depression, great recession, macroeconomics Tags: crowding out, Eugene Fama, fiscal policy, Treasury view of fiscal policy

Eugene Fama argues that government bailouts and stimulus plans seem attractive when there are idle resources – when there is unemployment such as in a recession or depression including in the 1930s.

Fama counters that:

1. Bailouts and stimulus plans must be financed.

2. If the financing takes the form of additional government debt, the added debt displaces other uses of the funds.

3. Thus, stimulus plans only enhance incomes when they move resources from less productive to more productive uses.

In the end, despite the existence of idle resources, bailouts and stimulus plans do not add to current resources in use. They just move resources from one use to another.

Fama noted that there was just one valid negative comment in response to this argument that appears to be valid which was made by Brad DeLong.

Fama thinks Delong’s point about involuntary inventory accumulation is consistent with Fama’s initial arguments about the need for the stimulus to work through moving resources to higher value uses.

For me, the notion that a fiscal stimulus is a negative productivity shock is a good starting point for analysis. The method of financing the stimulus is important too.

Economic agents know that a temporary expenditure program has no lasting effect on employment but has lasting effect on disposable income and taxes. Indeed, massive public interventions to maintain employment and investment during a financial crisis can, if they distort incentives enough, lead to a depression.

In Australia, there was a massive fiscal contraction from late 1930 onwards called the Premiers’ Plan. In 1931, unemployment rates was 25% or more.

- The Premiers’ Plan required the federal and state governments to cut spending by 20%, including cuts to wages and pensions and was to be accompanied by tax increases, reductions in interest on bank deposits and a 22.5% reduction in the interest the government paid on internal loans.

- The Premiers’ Plan was complementary to the Arbitration Court’s 10 per cent nominal wage cut in January 1931 and the devaluation of the Australian pound. Most countries had abandoned the gold standard by 1931 and 1932 and devalued by about 10% including the UK. These competitive devaluations were called currency wars. Most countries below started to recovery before they left the gold standard, a year or two before they left the cross of gold.

Maclaren (1936) dated the Australian economic recovery from the last months of 1932. It was to take another three years before unemployment rates fell below 10 per cent — the rate it had been during most of the 1920s.

The June 1931 Premiers’ Plan of fiscal consolidation had time by late 1932 to become credible and take hold given the usual leads and lag on fiscal policy. Unemployment data for the time show a rapid fall in the high twenties unemployment rate in 1932 to be below 10 per cent by 1937.

Milton Friedman on the onset of the Great Depression from the standpoint of 1930s macroeconomics

11 Jul 2014 Leave a comment

A different view of the start of Great Depression | Lee Ohanian

19 Jun 2014 Leave a comment

in great depression, macroeconomics Tags: great depression, Lee Ohanian, Milton Friedman

Friedman and Schwartz argue that the great depression was caused by a collapse of the money supply due to the negligence of the Fed that turned what should have been a garden-variety recession that started in late 1929.

Lee Ohanian argues that there was a steep industrial decline in the USA in 1929 began before monetary contractions or banking panics in 1930 and 1933. The figure below shows manufacturing industry hours worked between January 1929 and September 1930, and measures of the money stock from Friedman and Schwartz corresponding to M1 and M2. Manufacturing industry hours decline substantially and abruptly in late 1929 while money supply fall only about 4% and 1%, respectively.

This sharp decline in the manufacturing sector (a decline of nearly 30% by the fall of 1930 )began before monetary contraction or banking panics – the conventional culprits:

- There are no significant banking panics in 1929 and 1930. The banking panics in the great depression were mostly in 1933 and in 1934.

- Manufacturing hours worked had already fallen by 30% against trend by the time of the first banking panics in 1931, and these first banking panics had minor macroeconomic effects.

The data in the above figure shows that a factor other than monetary contractions or bank runs were central to the onset of the Great Depression.

Nominal wages declined by little during the early stages of the Depression. in September 1931 nominal wage rates were 92 per cent of their level two years earlier. Since a significant price deflation had occurred during these two years, real wages rose by 10 per cent during the same period, while gross domestic product fell by 27 per cent.

With a substantial depression in employment mostly in the manufacturing sector, any explanation of the onset of the great depression in the United States must start with an explanation of why the labour market failed to clear in that sector, why manufacturing decline was so immediately severe before significant monetary contraction and banking panics, why the Depression was so asymmetric across sectors, and provide a theory for why industrial sector wages were persistently well above their market-clearing level.

Just to make it harder for you,nominal wages in the agricultural sector will fell by 40% over the same period in which wages in the manufacturing sector did not fall to all. As Ohanian notes:

The Depression was the first time in the history of the US that wages did not fall during a period of significant deflation.”

Any explanation based on wage rigidity or sluggish wage adjustment or employee resistance to wage cuts must explain why this resistance was so effective in the manufacturing sector but so ineffective in the agricultural sector. Ohanian concluded that:

…the Depression is the consequence of government programs and policies, including those of Hoover, that increased labour’s ability to raise wages above their competitive levels.

Recent Comments