Richard Rogerson, Retirement, Home Production and Labor Supply Elasticities

13 Apr 2020 Leave a comment

by Jim Rose in human capital, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, occupational choice, poverty and inequality, unemployment Tags: economics of retirement, female labour force participation, health insurance, labour force participation, social insurance

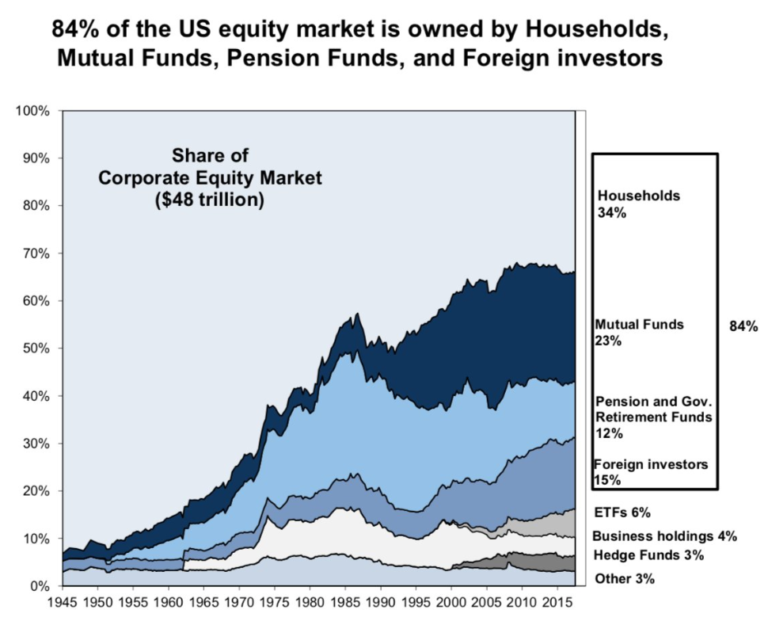

How is pension fund socialism going?

11 Apr 2020 Leave a comment

by Jim Rose in economic history, entrepreneurship, financial economics Tags: economics of retirement, pension fund socialism

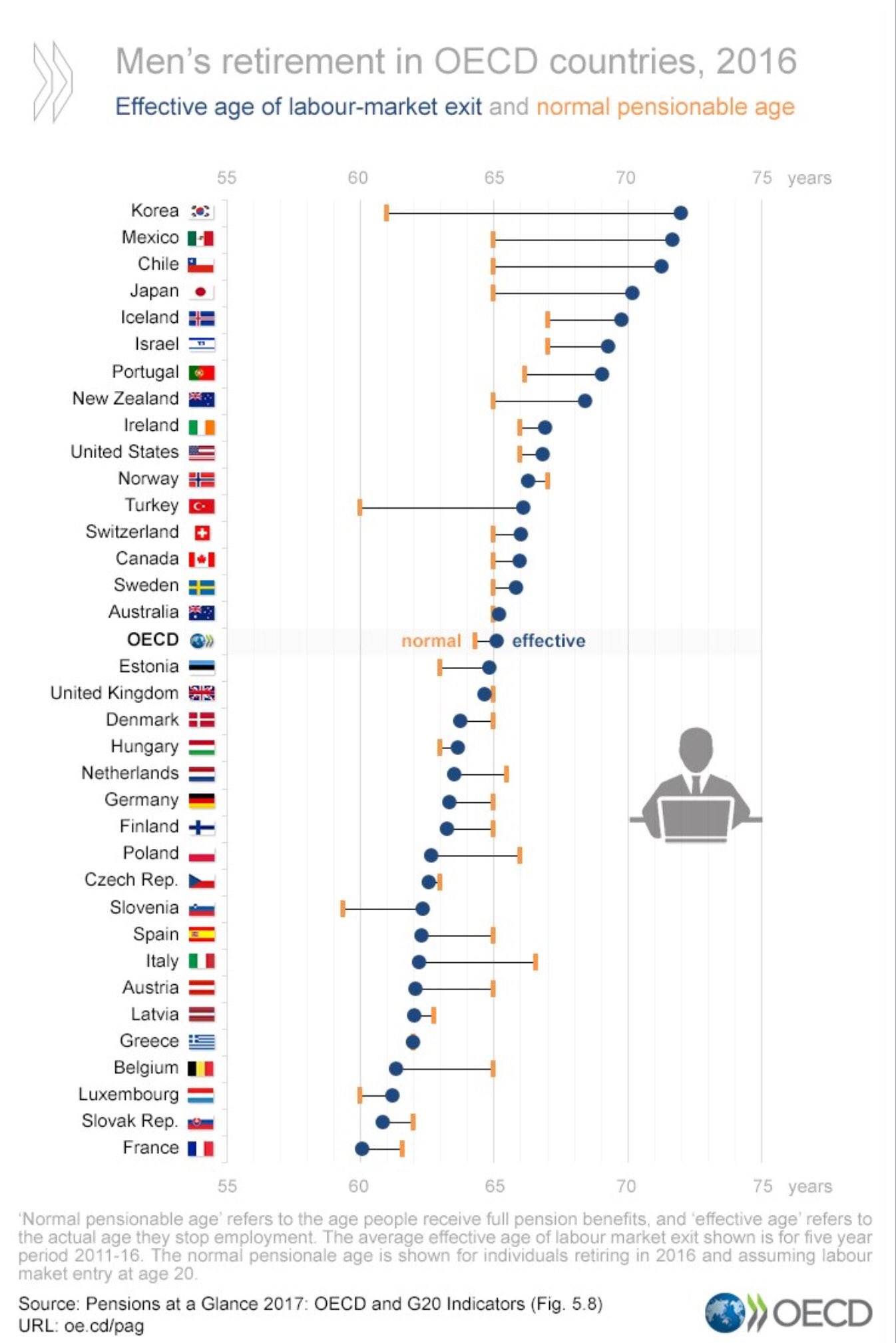

When do men retire

14 Dec 2017 Leave a comment

by Jim Rose in labour economics, labour supply Tags: economics of retirement

When men retire versus when they can take their pension. By country. Fascinating difference of (a) 12 years in retirement ages (b) countries where men retire before or after the pensionable age https://t.co/yMJAfC8Dc9 pic.twitter.com/gaq5jzuDdt

— Paul Kirby (@paul1kirby) December 10, 2017

Rate this:

Viagers as a way of funding retirements

12 Sep 2016 Leave a comment

by Jim Rose in labour economics, labour supply, poverty and inequality, welfare reform Tags: economics of retirement, French law, old age pensions, property law, reverse mortgages, social insurance

A Viager is a French way of buying and selling property. We just watched the Kelvin Klein – Maggie Smith movie about it.

Not only does the seller remain as a life tenant of the property they sold, the buyer pays them an annuity as well as a down payment. The buyer gambles as all annuity providers do on the life expectancy of the vendor. One such vendor lived to 123 in France.

Back in 1965, when Mrs Calment was aged 90, she sold her apartment in Arles to a 44-years old man, on contract-conditions that seemed reasonable given the value of the apartment and the life-expectancy statistics that prevailed at the time.

The man turned out to be unlucky since Jeanne Calment lived a very long life. He died in 1995, two years before Mrs Calment, after having paid about FFr900,000 (twice the market value) for an apartment he never lived in.

The viager system is similar to the equity release and reverse mortgage systems more familiar in Anglo-Saxon countries. The viager shares the risk of running out of equity with the buyer. The contract is between two private parties and does not involve banks or insurance companies.

Sellers are typically widows, or widowers, who want to cash out the value of their property with a lump sum – the bouquet – and a monthly payment from the buyer for the rest of their lives. The seller remains as a life tenant. The bouquet is normally 15-30% of the value of the property.

French viager investors tend to be in their late 40s and early 50s wanting to set themselves up with a retirement home and hopefully get a good deal. If the buyer dies before the seller his children will be obliged to carry on paying the viager if they want to maintain the deal. In that sense, the vendor is gambling on the buyer’s life expectancy is well.

I have no information on who is responsible for payment of rates and the maintenance of the property. The maintenance of the property would be a bigger moral hazard problem than with tenants because of the difficulties with eviction and repair. The market for Viagers is fairly small.

Should the buyer default on the monthly instalments, he is warned to pay up. After a second warning, normally within weeks, he will get a further warning and one month to get up to date with payments. If this does not happen the seller keeps keeps the bouquet, all money received so far and gets back absolute ownership of the property they sold.

This home annuity option for selling the house could be away of getting around the rather small to non-existent annuity market in New Zealand for retirees. They have the advantage of sharing the risk of exhausting the equity of the property at the price of the buyer sometimes gets a really good deal. Sellers have on average shorter survival times than the general French population.

Rate this:

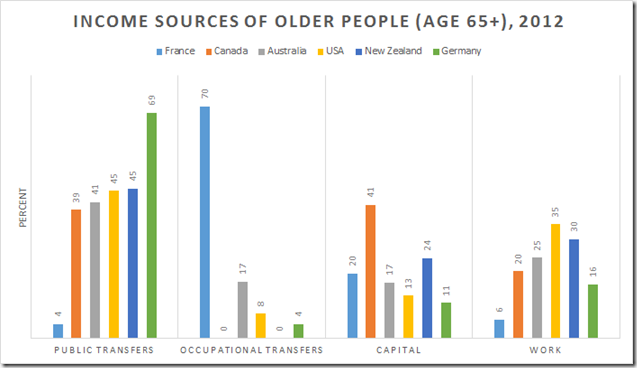

Income sources of older people in USA, Canada, France, Germany, Australia and New Zealand

18 Dec 2015 Leave a comment

by Jim Rose in labour economics, labour supply, public economics Tags: economics of retirement, old-age pension, older workers, social insurance, welfare state

Source: Pensions at a glance 2015 – © OECD 2015

Rate this:

Average effective retirement age by gender in the PIGS, 1970 – 2012

27 Jul 2015 Leave a comment

by Jim Rose in currency unions, economic history, Euro crisis, fiscal policy, labour economics, labour supply Tags: ageing society, demographics crisis, economics of retirement, female labour force participation, Greece, Italy, male labour force participation, old age pensions, older workers, Portugal, social insurance, Social Security, Spain, taxation and labour supply

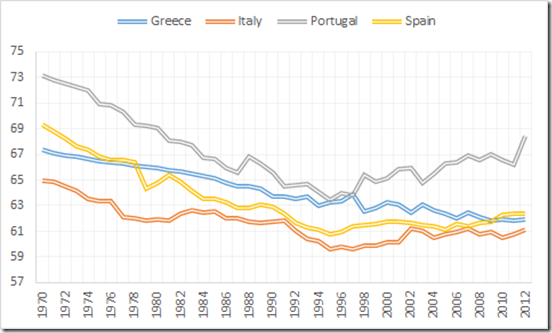

Figure 1 shows a relatively distinct pattern for men in the PIGs. Portugal aside, there has been a long decline retirement ages. This is different to the Anglo-Saxon countries where effective retirement ages have been increasing in recent years for men.

Figure 1: average effective retirement age (5-year averages), men, Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain, 1970 – 2012

Source: OECD Pensions at a Glance.

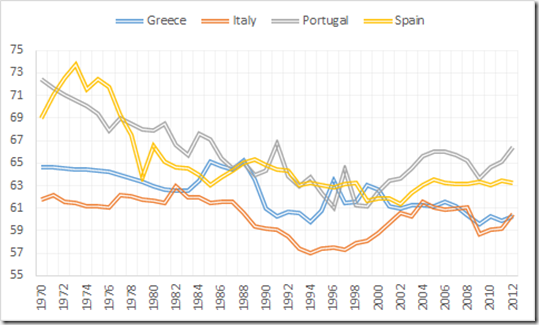

Figure 2 shows that apart from Greece, that after a long decline in female effective retirement ages, there was something the rebound, especially in Italy and Portugal. In Greece, the rebound was in the 80s, followed by a resumption of decline from the mid 90s.

Figure 2: average effective retirement age (5-year averages), women, Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain, 1970 – 2012

Source: OECD Pensions at a Glance.

Rate this:

Average effective retirement ages by gender in the USA, UK, Germany and France, 1970 – 2012

25 Jul 2015 1 Comment

by Jim Rose in economic history, gender, labour economics, labour supply, politics - USA Tags: ageing society, British economy, demographic crisis, economics of retirement, effective retirement ages, female labour force participation, female labour supply, France, Germany, male labour force participation, male labour supply, old age pensions, older workers, retirement ages, social insurance, Social Security, welfare state

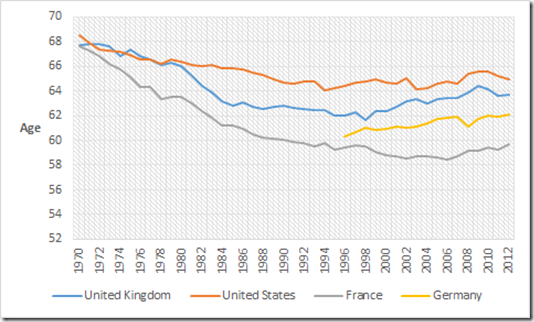

Figure 1 shows a divergence from a common starting point in 1974 effective retirement ages. The French in particular were the first to put their feet up and start retiring by the age of 60 by the early 1990. There was also a sharp increase in the average effective retirement age for men in the UK over a short decade. After that, British retirement ages for men started to climb again in the late 1990s. Figure 1 also shows that the gentle taper in the effective retirement age for American men stopped at the 1980s and started to climb again in the 2000s. The German data is too short to be of much use because of German unification. France only recently stopped seeing its effective retirement age fall and it is slightly increased recently – see figure 1

Figure 1: average effective retirement age for men, USA, UK, France and Germany, 1970 – 2012, (five-year average)

Source: OECD Pensions at a Glance.

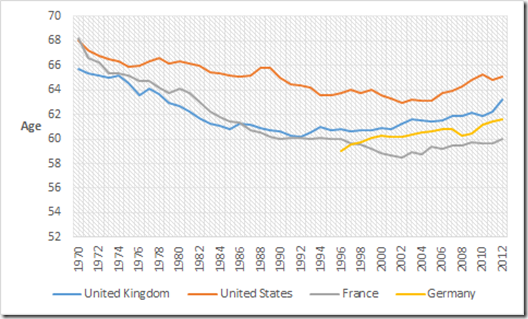

Figure 2 shows similar results for British and American women as for men in the same country shown in figure 1 . That is, falling effective retirement ages for both British and American women in the 1970s and 1980s followed by a slow climb again towards the end of 1990s. French effective retirement ages for women followed the same pattern as for French retirement ages for men – a long fall to below the age of 60 with a slight increase recently. The German retirement data suggest that effective retirement ages for German women is increasing.

Figure 2: average effective retirement age for women, USA, UK, France and Germany 1970 – 2012, (five-year average)

Source: OECD Pensions at a Glance.

Rate this:

Average effective retirement ages by gender, Australia and New Zealand, 1970 – 2012

24 Jul 2015 1 Comment

by Jim Rose in economic history, labour economics, labour supply, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand Tags: ageing society, Australia, demographic crisis, economics of retirement, effective retirement ages, female labour force participation, female labour supply, male labour force participation, male labour supply, old age pensions, older workers, retirement ages, social insurance, Social Security, welfare state

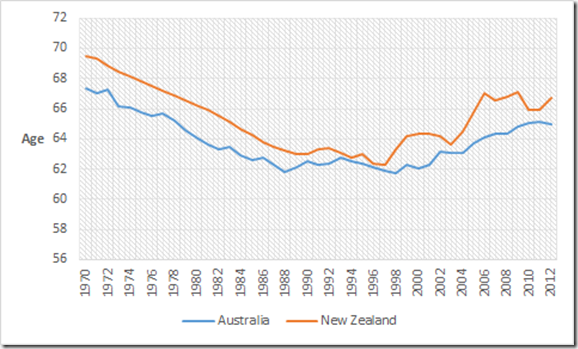

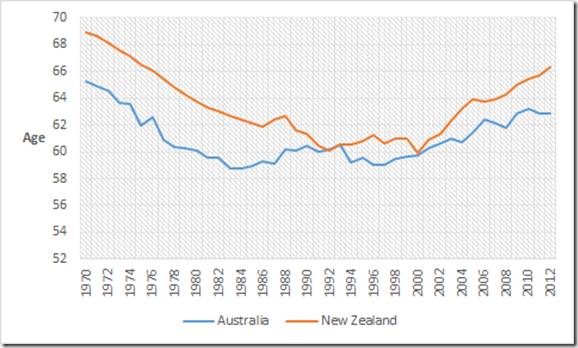

Figures 1 and 2 shows a sharp increase in the average effective retirement age for men and women in both Australia and New Zealand between 1970 and 1990. After that, retirement ages for men in both countries stabilised for about a decade. effective retirement age than Australia.

Figure 1: average effective retirement age for men, Australia and New Zealand, 1970 – 2012, (five-year average)

Source: OECD Pensions at a Glance.

Interestingly, in the 1970s and 1980s, New Zealand had an old-age pension scheme, known as New Zealand Superannuation, whose eligibility age was lowered from 65 to 60 in one shot in 1975. This old-age pension in New Zealand had no income test or assets test, but there was for a time a small surcharge on any income of pensioners. Nonetheless, New Zealand had a higher effective retirement age than in Australia where the old-age pension eligibility age is 65 with strict income and assets tests.

Figure 2: average effective retirement age for women, Australia and New Zealand, 1970 – 2012, (five-year average)

Source: OECD Pensions at a Glance.

Figure 1 and figure 2 also shows that the sharp increase in effective retirement ages in New Zealand for both men and women after the eligibility age for New Zealand’s old-age pension was increased from 60 to 65 over 10 years.

Figures 1 and 2 also show the gradual increase in effective retirement ages for Australian men and women from the end of the 1990s.

Rate this:

Average effective retirement ages by gender, USA and UK, 1970 – 2012

23 Jul 2015 Leave a comment

by Jim Rose in economic history, gender, labour economics, labour supply Tags: ageing society, British economy, demographic crisis, economics of retirement, effective retirement ages, female labour force participation, female labour supply, male labour force participation, male labour supply, old age pensions, older workers, retirement ages, social insurance, Social Security, welfare state

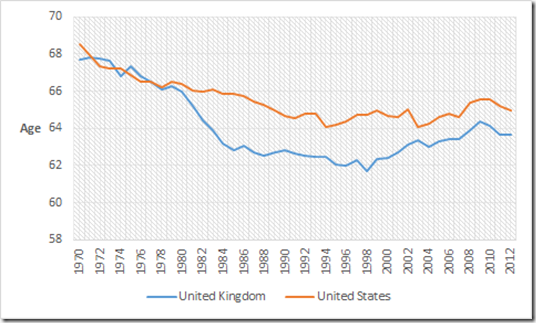

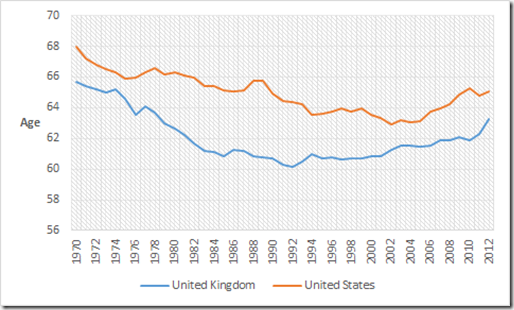

Figure 1 shows a divergence in the 1970s where there is a sharp increase in the average effective retirement age for men in the UK over a short decade. After that, British retirement ages for men started to climb again in the late 1990s. Figure 1 also shows that the gentle taper in the effective retirement age for American men stopped at the 1980s and started to climb again in the 2000s.

Figure 1: average effective retirement age for men, USA and UK, 1970 – 2012, (five-year average)

Source: OECD Pensions at a Glance.

Figure 2 shows similar results to figure 1 for British and American women. That is, falling effective retirement ages for both British and American women in the 1970s and 1980s followed by a slow climb again during the 1990s.

Figure 2: average effective retirement age for women, USA and UK, 1970 – 2012, (five-year average)

Source: OECD Pensions at a Glance.

Rate this:

Yet another gender gap that dare not speak its name

11 Apr 2015 Leave a comment

by Jim Rose in discrimination, gender, labour economics, labour supply Tags: ageing society, economics of retirement, labour demographics, reversing gender gap

Nearly half of baby boomers say they expect to work beyond 65

18 Mar 2015 Leave a comment

by Jim Rose in labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA Tags: ageing society, economics of retirement, labour demographics

Nearly half of baby boomers say they expect to work until age 66 or beyond: http://t.co/nJfwz7vaoc pic.twitter.com/ORhPdCgENL

— The Wall Street Journal (@WSJ) March 17, 2015

Rate this:

Recent Comments