Where on Earth is the Berlin wall? theguardian.com/cities/2014/oc… http://t.co/gE493huA8z—

Alberto Nardelli (@AlbertoNardelli) October 28, 2014

Where is the Berlin Wall now?

07 Nov 2015 Leave a comment

in entrepreneurship, liberalism, Marxist economics Tags: Berlin, entrepreneurial alertness, fall of berlin wall, fall of communism, Germany

German, French and Italian real housing prices since 1975

19 Oct 2015 Leave a comment

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economic history, economics of regulation, rentseeking, urban economics Tags: France, Germany, housing affordability, housing prices, Italy, land supply, land use planning, zoning

Source and notes: International House Price Database – Dallas Fed June 2015; nominal housing prices for each country is deflated by the personal consumption deflator for that country.

The territorial evolution of #Germany from 1867

21 Sep 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, war and peace Tags: economics of borders, Germany, World War I, World War II

No Generation Rent in #Deutschland! Real housing prices in #Germany, #France & #Italy since 1975

14 Sep 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, urban economics Tags: France, Generation Rent, Germany, housing affordability, housing prices, Italy, land supply, land use planning, NIMBYs, zoning

Source: International House Price Database – Dallas Fed

Note: The house price index series is an index constructed with nominal house price data. The real house price index is an index calculated by deflating the nominal house price series with a country’s personal consumption expenditure deflator.

Vanishing effect of #religion on the labour market participation of European women

19 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in economics of religion, gender, human capital, labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice, poverty and inequality, welfare reform Tags: female labour force participation, female labour supply, France, gender gap, Germany, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Turkey

Vanishing effect of #religion on the labor market participation of European women newsroom.iza.org/en/2015/08/10/… http://t.co/25nx8NiEfk—

IZA (@iza_bonn) August 10, 2015

Union density rates in Germany, France and Italy

14 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, Euro crisis, labour economics, unions, urban economics Tags: Eurosclerosis, France, German unification, Germany, Italy, union membership, union power, union wage premium

There are large differences in unionisation rates between the three countries. France has always had low levels of unionisation which halved since the 1970s. Italy had a sharp boost in union membership in the number of unions in the 1960s and 70s. This may have been associated with increased urbanisation. Union membership rate stayed pretty high in Italy ever since with a small taper downwards. Germany had stable unionisation rates prior to German unification after which the numbers about halved up in a slow taper.

Source: OECD Stat Extract.

German unemployment incidence by duration since 1983

11 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history, Euro crisis, fiscal policy, job search and matching, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, unemployment, welfare reform Tags: equilibrium unemployment rate, Eurosclerosis, German unification, Germany, natural unemployment rate, poverty traps, unemployment duration, unemployment insurance, welfare state

German long term unemployment has been pretty stable albeit with an up-and-down after German unification. There is also a fall in long-term unemployment after some labour market reforms around 2005.

Source: OECD StatExtract.

Modern European borders superimposed over Europe in 1914

06 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in defence economics, economic history, war and peace Tags: France, Germany, Russia, UK politics, World War I

Modern European borders superimposed over Europe in 1914 immediately before World War ! – bit.ly/1BCI17c http://t.co/0vADDCvp2l—

Brilliant Maps (@BrilliantMaps) December 12, 2014

Any progress ever on the gender wage gap in France, Germany, Sweden and Norway since 1980?

05 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in discrimination, economic history, gender, labour economics, law and economics Tags: France, gender wage gap, Germany, Leftover Left, Norway, Sweden, Twitter left

Our friends on the Left go on about how wonderful place Sweden is despite its gender gap being stuck for 35 years. Not much better in Norway and in Germany and France for that matter.

Figure 1: gender wage, % of median male wage, full-time employees, France, Germany, Sweden and Norway, 1980 – 2012

Source: Earnings and wages – Gender wage gap – OECD Data.

The gender wage gap in figure 1 is unadjusted and defined as the difference between median earnings of men and women relative to median earnings of men. Data refer to full-time employees.

Swedosclerosis, Eurosclerosis and the British disease compared

05 Aug 2015 2 Comments

in currency unions, economic growth, economic history, economics of regulation, Euro crisis, fiscal policy Tags: British disease, British economy, Eurosclerosis, France, Germany, Italy, sick man of Europe, Sweden, Swedosclerosis

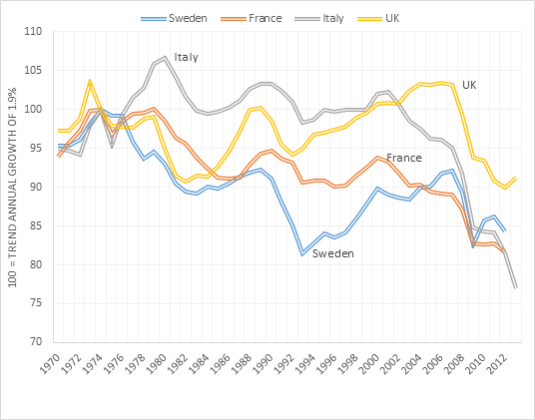

Figure 1 shows stark differences between Sweden, France, Italy and the UK since 1970 in departures from trend growth rates of 1.9% in real GDP per working age person, PPP. Italy did quite OK until 2000 growing at about the trend growth rate of 1.9% after which it fell into a hole so deep that it barely notice the onset of the global financial crisis. Sweden really had been the sick man of Europe until it turned its back on high taxing, welfare state socialism in the early 1990s. France has been in a long decline so much so that the global financial crisis is hard to pick up in the acceleration in its long decline in the mid-1990s. Figure 1 also shows Britain did very well, both under the neoliberal horrors of Thatcherism and the betrayals by Tony Blair of a true Labour Party platform. The UK grew at above the trend annual growth to 1.9% for most of the period from the early 1980s to 2007. The UK has done not so well since the onset of the global financial crisis.

Figure 1: Real GDP per Swede, French, British and Italian aged 15-64, 2014 US$ (converted to 2014 price level with updated 2011 PPPs), 1.9 per cent detrended, 1970-2013

Source: Computed from OECD StatExtract and The Conference Board. 2015. The Conference Board Total Economy Database™, May 2015, http://www.conference-board.org/data/economydatabase/

Note: When the line is flat, the economy is growing at its trend annual growth rate. A falling line means below trend annual growth; a rising line means of above trend annual growth. Detrended with values used by Edward Prescott.

German data was not in figure 1 because German unification threw all of its data into disarray for long-term comparison purposes.

Germany of 1871-1918

03 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in economic history Tags: Germany, maps, World War I

The Second German Empire or 'Reich' 1871-1918 – bit.ly/1yYKDGm http://t.co/fDTOlJRV0d—

Brilliant Maps (@BrilliantMaps) December 18, 2014

Tax rates on labour income across the OECD area

02 Aug 2015 Leave a comment

in labour economics, labour supply, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, public economics Tags: Australia, British economy, Canada, France, Germany, taxation and labour supply

How high is the US #tax burden on labor? Here's an OECD comparison tax.foundation/1KojUv9 by @samcjordan_ @kpomerleau http://t.co/fSAT8ut52z—

Tax Foundation (@taxfoundation) July 24, 2015

Strictness of employment protections for individual dismissals – USA, UK, France, Germany and the PIGS

28 Jul 2015 1 Comment

in Euro crisis, job search and matching, labour economics, law and economics, macroeconomics Tags: British economy, employment law, employment law regulation, Eurosclerosis, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain

Much easier to fire someone in the USA or UK than on continental Europe. Greece and Spain aren’t that bad by continental European standards for employment law protections against dismissals of individuals.

Figure 1: Strictness of employment protection for individual dismissals, 2013

Source: OECD StatExtract.

Recent Comments