25 Sep 2015

by Jim Rose

in economic history, income redistribution, politics - Australia, Public Choice, public economics

Tags: Australia, incidence of taxation, social insurance, taxation and entrepreneurship, taxation and investment, taxation and labour supply, top 1%, top tax rates, welfare state

21 Aug 2015

by Jim Rose

in applied price theory, business cycles, economic growth, economic history, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, public economics

Tags: Australia, British economy, productivity shocks, real business cycles, taxation and labour supply

Interesting to notice that in New Zealand and the USA after these increases in marginal tax rates on single taxpayers, their economies slowed down. What appears to have happened is a number of people reached the next income tax marginal tax rate threshold.

Source: OECD StatExtract.

19 Aug 2015

by Jim Rose

in economic growth, fiscal policy, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand

Tags: Australia, lost decades, marriage and divorce, productivity shocks, real business cycles, taxation and labour supply

In 2000 in New Zealand, the marginal tax rates of single earners, married couples and dual income couples were 21%.

Sources: OECD StatExtract.and OECD Taxing Wages.

Net personal marginal income tax rates increased:

- to 51% for one earner couples with two children in 2001 and stayed up above 50% until 2014; and

- to 33% for single earners with no children in 2004 because income growth pushed them into the next tax rate bracket which then dropped down to 30% in 2011.

Sources: OECD StatExtract.and OECD Taxing Wages.

Net personal marginal income tax rates increased:

- to 33% in 2004 for two earner couples with the second earner earning 33% of average earnings and then increased to 53% in 2006 and stayed high thereafter;

- to 33% in 2004 for a two earner couple with the second earner earning 67% of average earnings and then increased further to 53% in 2006 and stayed high until 2014 when their marginal income tax rate dropped to 30%; and

Sources: OECD StatExtract.and OECD Taxing Wages.

These large increases in marginal tax rates on single earners and families coincided with a slowing of the economy in about 2005. The economy started to pick up again when there were tax cuts introduced by the incoming National Party Government. Is that more than a coincidence?

Sources: Computed from OECD StatExtract and The Conference Board. 2015. The Conference Board Total Economy Database™, May 2015, http://www.conference-board.org/data/economydatabase/.

A flat line in the above figure is growth at the trend growth rate of 1.9% of the USA in the 20th century. A rising line is above trend growth for that year while a falling lined is below trend rate in GDP per working age person.

In the lost decades of New Zealand growth between 1974 In 1992, New Zealand lost 34% against trend growth which was never recovered. There was about 13 years of sustained growth at about the trend rate or slightly above that between 1992 and 2005. The entire income gap between Australia and New Zealand open up during these lost decades of growth between 1974 and 1992.

Sources: Computed from OECD StatExtract and The Conference Board. 2015. The Conference Board Total Economy Database™, May 2015, http://www.conference-board.org/data/economydatabase/.

Australia grew pretty much in its trend rate of growth since the 1950s. The so-called resources boom is not visible such as showing up as above trend rate growth.

17 Aug 2015

by Jim Rose

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economic growth, economic history, entrepreneurship, financial economics, fiscal policy, industrial organisation, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, politics - New Zealand, public economics

Tags: ageing society, company tax rate, deadweight cost of taxes, demographic crisis, efficient markets hypothesis, laffer curve, New Zealand superannuation fund, old age pensions, retirement savings, social insurance, sovereign wealth funds, taxation and entrepreneurship, taxation and investment, taxation and labour supply

The New Zealand Superannuation Fund, the sovereign wealth fund part funding New Zealand’s old-age pension from 2029/2030 onwards, has been a bit of a wild ride. Sometimes the earnings of the Fund were well below and sometimes earning well above the long-term bond rate.

![image_thumb[3] image_thumb[3]](https://utopiayouarestandinginit.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/image_thumb3_thumb.png?w=709&h=442)

Source: New Zealand Superannuation Fund Annual Report 2014.

Since its inception, the Fund earned an average annual return of 9.78%, which was 5.06% above the long-term bond rate, and 1.03% above its reference portfolio.

No information was given in the annual report of the New Zealand Superannuation Fund on the marginal dead weight cost of the taxes raised to fund the New Zealand Superannuation Fund to see whether there is any net benefit to taxpayers from its establishment and continued operation.

The New Zealand Government has contributed $14.88 billion to the fund from prior its inception in 2001 to the suspension of contributions in 2009 by the incoming National Party Government.

Source: New Zealand Treasury.

Over the nine years in which contributions were made, the company tax rate of 28% could have easily been up to 10 percentage points lower.

The New Zealand Treasury estimates that a one percentage point cut in the company tax costs about $220 million in forgone revenue if there are no other changes to the tax system. These are static estimates that do not include any feedback from greater investment and higher growth.

The New Zealand Superannuation Fund must beat the market every single year to make up for the deadweight cost of its funding, a premium for the investment risk added to the Crown’s portfolio and the cost to New Zealand’s growth rate of higher than otherwise taxes on income, entrepreneurship and investment.

Source: Abolish the Corporate Income Tax – The New York Times.

16 Aug 2015

by Jim Rose

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, economic growth, fiscal policy, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics

Tags: Eurosclerosis, Frantz, social insurance, taxation and entrepreneurship, taxation and investment, taxation and labour supply, unemployment insurance, welfare state

10 Aug 2015

by Jim Rose

in applied price theory, applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, currency unions, economic growth, economic history, economics of regulation, entrepreneurship, Euro crisis, fiscal policy, global financial crisis (GFC), income redistribution, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, Marxist economics, poverty and inequality, Public Choice, public economics, rentseeking

Tags: British disease, entrepreneurial alertness, Eurosclerosis, France, German unification, Germany, growth of government, sick man of Europe, social insurance, Sweden, taxation and entrepreneurship, taxation and investment, taxation and labour supply, welfare state

The Washington Centre for Equitable Growth recently tweeted that inequality harms growth in the USA as compared to Sweden, France, Germany and the UK. It was relying on some dodgy OECD research.

The Washington Centre for Equitable Growth did not check their inequality ratios they tweeted against trends in economic growth and economic policy since 1970, which I have reproduced in figure 1. Germany is not included in figure 1 because German data on growth is thrown askew by German unification.

Figure 1: Real GDP per British, French and Swede aged 15-64, 2014 US$ (converted to 2014 price level with updated 2011 PPPs), 1.9 per cent detrended, 1970-2013

Source: Computed from OECD Stat Extract and The Conference Board. 2015. The Conference Board Total Economy Database™, May 2015, http://www.conference-board.org/data/economydatabase/

Figure 1 shows that France has been in a long-term decline since the late 1970s despite the blessings of a more equal society than the USA as championed by the Washington Centre for Equitable Growth. In figure 1, a flat line is growth in real GDP per working age person, PPP, at the same rate as the USA for the 20th century, which was 1.9% per year. A falling line in figure 1 indicates growth of less than 1.9% while a rising line indicates growth in real GDP per working age person, PPP, in excess of 1.9%. In figure 1, France hardly ever grew at the trend rate of growth for the USA of 1.9% per year and was frequently well below that rate.

Sweden tells a slightly different story in figure 1 because of regime change in the early 1990s when Sweden adopted more liberal economic policies where taxes and government spending were reduced:

The rapid growth of the state in the late 1960s and 1970s led to a large decline in Sweden’s relative economic performance. In 1975, Sweden was the 4th richest industrialised country in terms of GDP per head. By 1993, it had fallen to 14th.

That regime change reversed a long economic decline since 1970 under the egalitarian policies of the Swedish Social Democratic Party. Under the Swedish Social Democratic Party, Sweden was almost always growing at less than the trend rate of growth of the USA, which was 1.9%. That position reversed only when there was a turn away from big government and high taxes.

Figure 1 tells a similar story for the British economy: a long economic decline in the 1970s when Britain was the sick man of Europe. Under Thatchernomics, Europe had a long economic boom for 20 years or more – see figure 1.

In the 1970s, under the high taxes of the Heath, Callaghan and Wilson administrations, as figure 1 shows, Britain was the sick man of Europe. With the election of the Thatcher Government, Britain soon grew at better than the US trend growth rate for nearly 20 years through few exceptions.

10 Aug 2015

by Jim Rose

in applied welfare economics, comparative institutional analysis, economic growth, economic history, economics of regulation, industrial organisation, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, survivor principle

Tags: Eurosclerosis, Sweden, taxation and entrepreneurship, taxation and investment, taxation and labour supply, welfare state

08 Aug 2015

by Jim Rose

in budget deficits, great recession, job search and matching, labour economics, labour supply, macroeconomics, politics - USA, unemployment, welfare reform

Tags: natural unemployment rate, taxation and labour supply, unemployment duration, unemployment insurance, unemployment rates, welfare state

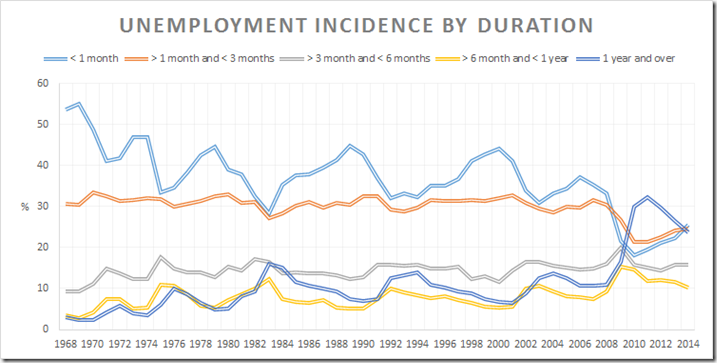

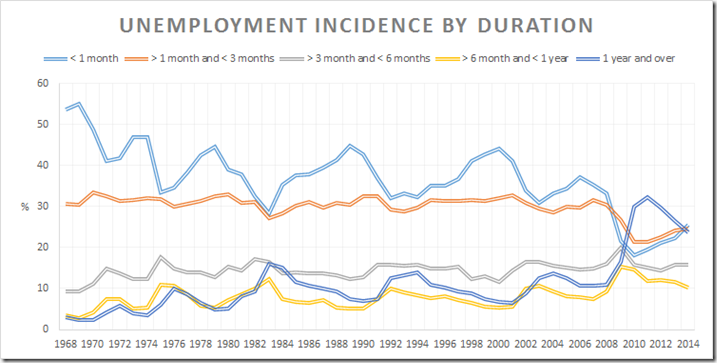

The Great Recession was the first recession in the USA in a good 40 to 50 years where the composition of employment changed by much. Even the big recession at the beginning of the 1980s did not do much to the composition of unemployment by duration in the USA.

Source: OECD StatExtract.

Those unemployed for more than a year moved from barely double digits even in a bad recession prior to 2008 to coming on one-third of all unemployed. Likewise, those unemployed for less than a month halved from 40% to 20%. Something changed in the US labour market with the Great Recession and the long extensions of unemployment insurance from 26 weeks to 52 weeks and then 99 weeks.

03 Aug 2015

by Jim Rose

in labour economics, labour supply, occupational choice, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, poverty and inequality, unemployment, welfare reform

Tags: social insurance, taxation and labour supply, unemployment benefits, welfare reform

02 Aug 2015

by Jim Rose

in labour economics, labour supply, politics - Australia, politics - New Zealand, politics - USA, public economics

Tags: Australia, British economy, Canada, France, Germany, taxation and labour supply

27 Jul 2015

by Jim Rose

in currency unions, economic history, Euro crisis, fiscal policy, labour economics, labour supply

Tags: ageing society, demographics crisis, economics of retirement, female labour force participation, Greece, Italy, male labour force participation, old age pensions, older workers, Portugal, social insurance, Social Security, Spain, taxation and labour supply

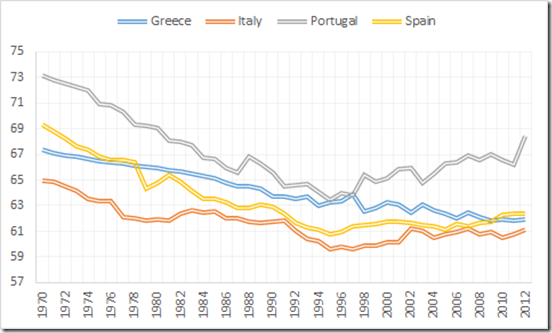

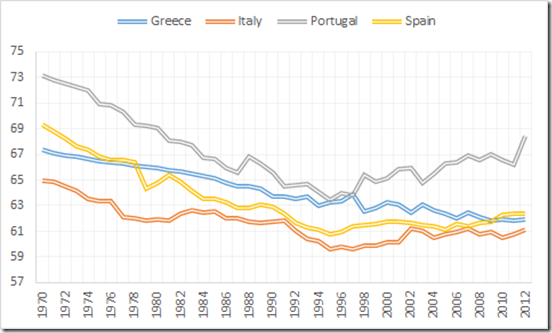

Figure 1 shows a relatively distinct pattern for men in the PIGs. Portugal aside, there has been a long decline retirement ages. This is different to the Anglo-Saxon countries where effective retirement ages have been increasing in recent years for men.

Figure 1: average effective retirement age (5-year averages), men, Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain, 1970 – 2012

Source: OECD Pensions at a Glance.

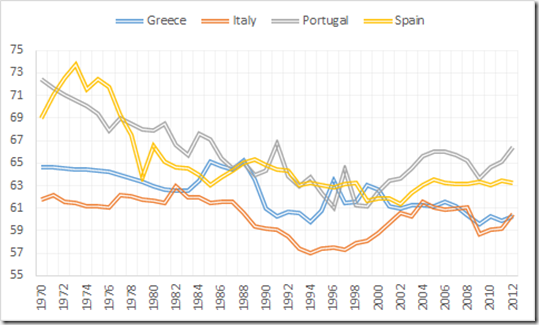

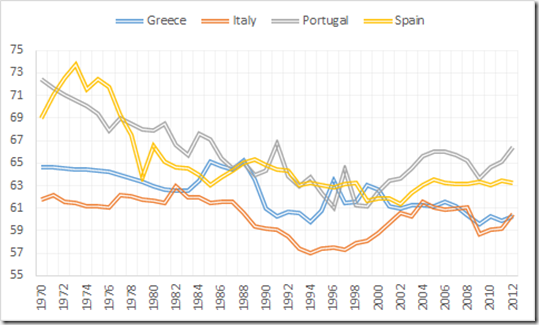

Figure 2 shows that apart from Greece, that after a long decline in female effective retirement ages, there was something the rebound, especially in Italy and Portugal. In Greece, the rebound was in the 80s, followed by a resumption of decline from the mid 90s.

Figure 2: average effective retirement age (5-year averages), women, Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain, 1970 – 2012

Source: OECD Pensions at a Glance.

Previous Older Entries Next Newer Entries

![image_thumb[3] image_thumb[3]](https://utopiayouarestandinginit.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/image_thumb3_thumb.png?w=709&h=442)

Recent Comments